Executive summary

Workplace conflict context at East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust

In recent years, the NHS has become a centre of innovation in conflict management. It has been the subject of a series of research case studies for Acas looking at the management of workplace conflict in Britain, of which this report is the latest. It provides the findings of a qualitative case study evaluation of attempts by East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust (ELHT) – an acute NHS Trust is located in North West England – to build on an existing internal workplace mediation scheme and develop a more systemic approach to early conflict resolution.

Prior to 2016, conflict within the Trust was widespread and its management was characterised by risk-averse and adversarial approaches that revolved around the rigid application of conventional procedures. Conflict was characterised by the breakdown of relationships and long-term absences from work.

Respondents described a culture in which staff found it difficult to speak up. At the same time, managers did not have the skills and confidence needed to address problems such as poor performance. Consequently, managers tended to avoid conflict and relationships between key stakeholders lacked the levels of trust needed to support early and informal processes of resolution.

The original internal mediation service (located in HR) was under-resourced and difficult to access. There was little organisational commitment to mediation and staff viewed it with scepticism. It tended to be used as a last resort and was typically an outcome of grievance or disciplinary procedure.

The Trust's response to conflict management challenges

East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust's response to these challenges has been threefold, with evidence that these 3 initiatives were a key part of a wider strategic goal of building a culture of "kindness and compassion":

1. Renewed investment in, and commitment to, workplace mediation

A new cadre of mediators were trained, drawn from key stakeholder groups. Dedicated time and space was provided to mediators and a full-time coordinator was appointed. The mediation service was also relocated from HR to occupational health, underlining the link between dispute resolution and wellbeing.

2. Introduction of a new Early Resolution Policy

The Early Resolution Policy essentially replaces the existing grievance and bullying and harassment policies. This does not preclude employees making a formal complaint but ensures that other forms of resolution are considered. Concerns can be channelled through line managers, freedom to speak guardians, trade unions, HR practitioners or occupational health or a combination of these.

This triggers conversations between the individuals and key stakeholders themselves and creates space for a wider range of interventions which can include mediation, training, coaching or team facilitation.

This Early Resolution Policy does not replace disciplinary policy and procedure or those related to managing performance or attendance. However, in respect of these issues the Trust makes it clear that there should be a "greater focus on informal remedy". (East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust Disciplinary Policy and Procedure, ELHT HR09 version 8, page 2).

3. Increased focus on developing managerial skills

A structured management training programme, called 'Engaging Managers', was developed, which recognised the need for improved people management capabilities. This also acknowledged that a focus on leadership development had diverted attention away from managerial skills.

However, it was recognised that rolling out management training faced a number of challenges given the pressure on staff time, competing priorities and, more recently, the covid-19 (coronavirus) pandemic.

Impacts of the Trust's responses

Workplace mediation

The first of these, the redevelopment of the mediation service, saw the number of individual and group mediations increase, with a reported resolution rate of over 90%.

Research respondents across the Trust were largely positive about the use of mediation, which was seen as more efficient than formal procedures but also more likely to repair employment relationships and avoid long-term absence and staff turnover. Respondents also identified wider positive impacts on the day-to-day practice of those involved in the mediation process.

The experiences of mediation participants were more nuanced. Those who were managers sometimes felt compelled to attend, which raises questions about the longer-term sustainability of agreements reached.

In addition, it could be argued that the content of mediation agreements often reflected basic managerial actions, such as one-to-ones between line managers and their direct reports, which could have been addressed outside the mediation process. There is therefore a danger that mediation becomes a default option, deflecting the focus from poor management practice.

Early Resolution Policy

The second initiative – the Early Resolution Policy – was generally seen as a positive development by HR practitioners, union representatives and those managers within the sample. It had the potential to deliver 3 key benefits.

First, it could help to explain informal resolution in practical terms, something that was often unclear to managers and their staff. Second, it placed a clear expectation on managers that they should use informal approaches to conflict resolution wherever possible and appropriate. Third, the policy represented a cultural shift away from allocating blame towards a focus on outcomes and resolution.

Although it is difficult to measure the impact of different aspects of the Trust's conflict management and employee engagement strategies, there was tentative evidence of a shift towards earlier and informal resolution and more collaborative approaches.

In total, between January 2019 and July 2022, 223 cases had been referred to the Early Resolution Policy and 188 had been concluded. Of these, nearly three-quarters were resolved informally and only 22% progressed to formal procedures.

Nonetheless, while the Policy had been embraced by certain parts of the organisation, in others approaches to conflict management still revolved around procedural compliance. There were also concerns that the discretion offered by the policy could be confusing for some managers, particularly those who lacked conflict confidence.

Furthermore, there was a risk that these managers could be deterred from taking early action themselves to address or resolve an issue.

Developing managerial skills

With regard to the third initiative – the 'Engaging Managers' training programme – although there was agreement that managerial skills have improved over the last 5 years, a lack of conflict confidence and capability was still widely cited by respondents and would appear to be the main factors limiting the development and impact of early resolution at the Trust.

This lack of confidence not only creates resistance to early resolution, but makes it difficult to achieve a balance between different elements of the Trust's approach to conflict management.

The findings in this report have to be viewed in the context of the covid pandemic that overshadowed this research. Although the initial consequences for the management of conflict were mixed, in the longer term, the pandemic is likely to have had a significant and profound impact on the wellbeing of staff at the Trust, in common with NHS organisations across the UK.

This in turn is likely to be reflected in the quality of employment relationships and increased pressure on managers to be able to manage and resolve conflict. Fundamentally, we would argue the pandemic has exposed the need to place the wellbeing and engagement of staff at the centre of organisational strategy, as demonstrated by the Trust's increased health and wellbeing provision and focus.

This report highlights the benefits of internal workplace mediation and the potential of a structured approach to early conflict resolution. However, the findings also suggest that to maximise the impact of an early resolution policy, if implemented in similar organisations, a number of issues need to be considered.

First, building the conflict confidence and competence of line and middle managers is critical.

Second, there is a need for multiple channels of resolution, which should include rights-based procedures alongside interest-based processes such as mediation.

Third, there needs to be a systemic approach to integrating these mechanisms, underpinned by a strategic commitment to conflict management.

Finally, clear communication of the policy is vital in order to engage those involved in operationalising dispute resolution, particularly line managers.

1. Introduction

The need for a new approach to workplace dispute resolution has become a central focus of public employment policy (Gibbons, 2007). In particular, it has been consistently argued that more emphasis needs to be placed on early responses to individual employment conflict and the increased use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) (BIS, 2011).

Interest in workplace mediation has certainly grown over the last decade, alongside an expanding evidence base that points to its potential benefits. Mediation has been found to provide an efficient and effective way of resolving disputes when compared with conventional rights-based approaches. Moreover, it has been argued that mediation can have positive 'upstream' effects and act as a catalyst for improvements in the way that organisations manage individual conflict (CIPD, March 2015; Hann and Nash, 2020; Saundry et al, 2016).

However, the extent to which this has been accompanied by a broader shift towards earlier and less formal approaches to conflict management is questionable. Although the importance of early resolution has become embedded in the discourse of HR professionals (Hann and Nash, 2019; Saundry et al, 2020), the largest qualitative exploration of the management of conflict in UK workplaces to date concluded that this "rhetoric of early resolution does not appear to have transferred to the reality of managerial practice" (Saundry et al, 2016:46).

This has triggered a lively debate within the HR profession over the efficacy of conventional disputes processes with some commentators calling for a radical shift away from the use of conventional grievance procedures (Liddle, 2017).

One explanation for the lack of conflict management innovation in the UK has been the failure of many organisations to recognise it as a strategic priority (Roche et al, 2019). This is not necessarily the case within the NHS, where factors including regulatory and public scrutiny over patient care have arguably provided the basis for reform through a range of initiatives including: the development of internal workplace mediation services, conflict management systems, Freedom To Speak Up Guardians and 'Just and Learning Cultures'. However, there is, to date, limited robust evidence on the extent and impact of these approaches (Saundry, 2020).

In this context, this report attempts to evaluate the attempts by one acute NHS Trust to build on an existing internal workplace mediation service to develop a more systemic approach to early conflict resolution.

East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust (ELHT) is located in North West England. It was established in 2003 and is a large integrated health care organisation providing acute secondary healthcare. The Trust employs 8,000 staff and treats more than 700,000 patients at 5 hospitals and other sites in the community.

In September 2016, the Trust redesigned its approach to workplace mediation and conflict resolution with the aim of improving staff health and wellbeing and reducing the impact of workplace conflict on service delivery and patient care.

An existing internal mediation service was redeveloped: new mediators were trained, a coordinator was appointed, the referral process was streamlined, and the service was transferred into the Occupational Health and Well-Being department. Between September 2016 and May 2021 there were 142 mediations, 135 of which resulted in an initial agreement; a resolution rate of 95%. There were also 9 group mediations, all of which reached an agreement.

More recently this approach has been developed to embed informal resolution with a focus on bullying and harassment cases. This is part of a wider commitment to 'compassionate and inclusive leadership', which reflects broader trends within the NHS.

Consequently, the grievance and bullying and harassment policies have been combined into one which focuses on early resolution and support for staff to develop and learn. This was developed in partnership with HR, occupational health, trade unions, and also the Trust's Staff Guardian.

The new Early Resolution Policy was launched in January 2019. Although this policy does not replace those on disciplinary action, managing performance or attendance, the Trust states there should be a "greater focus on informal remedy" (East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust Disciplinary Policy and Procedure, ELHT/HR09 version 8, page 2).

Therefore, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust provides a context in which we can not only examine the operation of internal workplace mediation but also the development of a distinctive early resolution policy and process, an approach which has not been the subject of independent academic research.

This will provide vital insights for policymakers and practitioners in designing similar initiatives. Furthermore, as the research has straddled the covid pandemic, it enables an assessment of the capacity of an organisation to manage conflict when under severe and exceptional pressure. Consequently, this report:

- examines the development of workplace mediation within the Trust

- assesses the benefits of workplace mediation in relation to the resolution of individual disputes and the wider impact of the operation of the mediation service on the management of conflict and employment relations

- examines the rationale and development of the Trust's move towards an early resolution approach, which mediation is part of

- investigates the management of discipline and grievance within the Trust

- examines the introduction and implementation of the Trust's Early Resolution Policy

2. Mediation and early resolution

In recent years, the erosion of collective employment relations, and specifically the role played by collective bargaining in resolving conflict, has increased the focus on various forms of alternative dispute resolution, and in particular workplace mediation.

This has been most apparent in the USA, where more than 4 out of 5 Fortune 1000 companies reported using mediation in 2011 (Lipsky et al, 2014). In the UK the evidence is uneven, but a representative survey from the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) suggested mediation was used by around one-third of employers (CIPD, April 2015).

The increased use of mediation in the UK has largely been driven by demands for reduced costs and greater efficiency. In this context, workplace mediation arguably offered workplaces experiencing high levels of conflict a cost-efficient alternative to conventional disciplinary and grievance procedures (Latreille, 2011; Saundry et al, 2011; Wood et al, 2017).

Although quantifying the cost advantages of mediation has been notoriously problematic, some basic comparisons with conventional disciplinary and grievance procedures in the UK suggest it uses fewer organisational resources and is more likely to preserve and repair employment relationships (Latreille, 2011; Saundry et al, 2011).

However, it is also, in part at least, a response to the greater policy emphasis on early and less formal approaches to resolution. Following the Gibbons review of the UK's system of employment dispute resolution in 2007, the government introduced a number of measures designed to encourage informal resolution and the use of alternative dispute resolution (Saundry and Dix, 2014).

These included the 2009 revision of the Acas Code of Practice on disciplinary and grievance procedures, which specifically promoted the use of mediation for the first time. Rahim et al's (2011) evaluation of the introduction of the revised Code found that "the introduction of mediation into an organisational approach was prompted by a review of policies in light of the Code" (page 40).

Furthermore, evidence from the UK does point to the wider benefits of workplace mediation. Saundry et al's study of the experiences of mediation participants (2013:3) found that mediation prompted managers to reflect on and reassess their relationships with staff and the impact of their managerial styles and behaviours.

Importantly, one of the earliest evaluations of mediation undertaken in the UK focused on East Lancashire Primary Care Trust (PDF, 579KB), which was subsequently merged into East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust, the subject of this current case study. A 2011 study found evidence that the introduction of an internal mediation service had a transformative impact on employment relations and stimulated early and informal conflict resolution (Saundry, McArdle and Thomas, 2011).

The research also pointed to the importance of the design of in-house mediation schemes. In particular, locating the service outside the direct control of HR, drawing on mediators from across the organisation, including trade unions, and senior leadership support were all seen to be key ingredients in maximising mediation impact. The ongoing impacts will be discussed within this current study from section 4 onwards.

The persistence of risk-averse and compliance-based approaches to workplace conflict has led some commentators (Liddle, 2017) to call for conventional disciplinary and grievance procedures to be replaced by processes that focus on resolution. Indeed, at a rhetorical level, these arguments are being increasingly heard at all levels of the HR profession.

However, there is as yet little evidence that alternative approaches have been widely adopted and there has been no independent academic research into the effectiveness of early resolution processes.

Additionally, in the UK, there is little academic evidence of the widespread introduction of integrated conflict management systems (Hann and Nash, 2020); these are systems that combine complementary alternative dispute resolution practices with rights-based processes (Bendersky, 2003; Lipsky et al, 2003) to create an environment and culture which encourages managers to address, contain and resolve conflict at the earliest possible stage. More than a decade after the Gibbons Review, a lack of managerial capability and increasingly remote models of HR advice (Saundry et al, 2019) means that early resolution remains a distant goal for many.

However, there are some notable exceptions to this and there is evidence that the NHS has become a centre of innovation (Latreille and Saundry, 2015). One such innovation across the NHS is the introduction of Freedom To Speak Up Guardians, developed as a consequence of the Francis (2015) Freedom To Speak Up Review.

This aimed to enable the NHS to learn from problems and potential problems, and then make improvements and reduce harm. Freedom To Speak Up Guardians are trained individuals within a Trust to whom staff can safely disclose worries about patient care or staff members' working environments. The Freedom To Speak Up Guardian will then support the staff member in this concern being addressed, in a timely, consistent and effective manner with a range of resources and channels available within and outside a Trust.

Another important initiative was the development of an integrated approach to conflict management within Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (PDF, 611KB). This revolved around the ongoing analysis of organisational data to identify conflict hotspots. Mediation capacity was then used flexibly to address these problems through mediation, conflict coaching and group facilitations (Latreille and Saundry, 2015).

Importantly, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust also placed a significant emphasis on developing conflict competence among managers through compulsory training in 'difficult conversations'. Latreille and Saundry found not only high levels of awareness of mediation among managers but also collaborative styles of conflict management.

The introduction of the conflict management system at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust was also seen to be a major factor in a significant improvement in outcomes in terms of staff engagement and the incidence of bullying and harassment.

A survey of the impact of covid on employment relations within the NHS (Saundry, 2020) found further evidence of conflict management innovation, with 85% of organisations reporting having Freedom To Speak Up Guardians, while just under 8 in 10 had in-house trained mediators.

More than 1 in 3 organisations responding to the survey had also developed a 'Just and Learning Culture' – an approach designed to avoid unnecessary disciplinary suspensions and promote 'compassion and kindness' in the way that organisations respond to difficult issues and critical incidents.

However, the same study concluded that these initiatives were not always integrated into systemic and strategic approaches. While there was a clear desire to embrace early conflict resolution, the reality was somewhat different.

Three-quarters of respondents still felt that disciplinary and grievance issues were often bogged down in lengthy procedures. This was not helped by an aversion among some HR practitioners to proactive and creative resolutions compared to the relative safety of procedural and legal compliance.

In addition, there were widespread concerns as to whether managers, often working under intense operational pressure, had the skills and confidence they needed to deal with complex people management challenges (Saundry, 2020).

Many of these findings were reinforced by a follow-on study in 2022, as the NHS emerged from the height of the pandemic and into a "new normal" for people management (Bennett et al, 2022).

Line managers' capability and capacity were reported as the top cause of conflict, and 67% of respondents thought that managers were not well equipped to identify and resolve difficult issues, while 44% suggested that managers would not deal with issues fairly or effectively.

In terms of dealing with workplace conflict, a culture based on an informal and restorative approach to dispute resolution was seen as most appropriate. The survey revealed that the top solutions were:

- an informal resolution policy

- mediation

- a 'Just and Learning Culture'

To further understand employee relations in the NHS and their innovative approaches, this study seeks to explore the development of early resolution within East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust and to provide an early assessment of its impact by means of a qualitative case study design.

3. Methodology

This report provides findings from the project which consists of an in-depth exploratory case study with the following elements:

Semi-structured interviews with key gate-keepers and stakeholders

This includes interviews with senior staff across Health and Well-Being, mediation, management, HR and staff-side and trade unions. 8 interviews were conducted, taking on average 45 minutes each, making almost 7 hours in total.

An examination of documentation regarding individual dispute resolution

This includes current and previous policies and procedures relating to grievance, discipline, capability, and bullying and harassment.

Analysis of available statistical data

This includes:

- data regarding numbers of disciplinary, grievance and bullying and harassment cases

- mediation numbers and outcomes

- results of the NHS staff survey

Semi-structured interviews with staff involved in the resolution of individual disputes

Such as operational managers, trade union representatives, HR practitioners, mediators and mediation participants and disputants. 22 interviews were conducted, on average 45 minutes long, making almost 19 hours in total.

Unfortunately, the scheduled research coincided with the covid outbreak and therefore the project design was adapted to enable the Trust to participate in the research when they deemed appropriate and to protect all those involved in the research.

The fieldwork started in spring 2020 with stakeholder interviews, and was then paused until summer 2021 to conduct further interviews. Overall, 30 interviews were conducted via telephone and video, comprising almost 26 hours of data.

4. Background

In 2013, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust was one of 14 NHS hospital trusts included in the Keogh Review as a result of persistently high mortality rates (Keogh, 2013). While the review team identified a number of areas of good practice and highlighted the dedication of staff, it also raised a number of concerns including the quality of governance processes.

As a consequence, the Trust was placed into special measures and the chief executive, chair and deputy chair resigned their posts. In the 2013 NHS staff survey, the Trust performed worse than expected for staff recommending the Trust as a place to work or receive treatment, experiencing discrimination at work in the last 12 months and experiencing harassment, bullying or abuse from patients, relatives or the public in the last 12 months.

In July 2014, an inspection by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) judged that "Trust leadership" "required improvement" despite some evidence of progress since 2013.

Importantly the Trust simplified its vision "to be widely recognised for providing safe, personal and effective care" and this still guides the people strategy of the Trust today. In particular, the Care Quality Commission found that staff felt there had been very positive changes in relation to the culture of the organisation and felt supported and empowered to make decisions and highlight concerns.

Our research suggests that Keogh had triggered a series of important changes and particularly a wholesale change of senior leadership. One respondent explained this as follows:

"We were under a huge amount of scrutiny in 2013 which really held a mirror up to ourselves as an organisation and that meant that we got a whole new executive leadership function...and that gave us an opportunity to be really honest about the culture within the organisation…

"We got a new chief executive and a new director of HR and they had a very different leadership approach, very much around compassionate and inclusive leadership." – interview 31.

In April 2014, the Trust started 'the Big Conversations', a staff engagement exercise aimed at listening to staff concerns and understanding the challenges they faced. Among other things, this exercise revealed that conflict was a key issue. This was also reflected in the number of cases that were being referred through the occupational health service, many of which had their roots in relationship problems in the workplace.

5. Before: formality, conflict and compliance

Respondents argued that, prior to 2016, conflict was commonplace and was managed in a traditional way, centred around the application of lengthy and complex processes and procedures.

"It was very old school…traditional, much more formal policy process. You tick this box, we've followed this process. So, there wasn't much latitude or interest in deviating from that" – interview 31.

Moreover, the application of formal process had a range of negative impacts on those involved and also on the Trust:

"[there] was quite a high volume of quite long-standing employee relations issues where teams just weren't getting on… people being off sick for long periods and real difficulties…and it felt at that time like we launched into process before we tried to do any of the banging heads together." – interview 27.

Nonetheless, these approaches were still supported by key constituencies within the Trust, although for very different reasons. For example, there was an emphasis in HR on procedural compliance and risk management, which blocked more informal and creative solutions to problems.

This was underpinned by a lack of confidence in, and among, managers to handle employment issues. An example commonly cited was clinicians being promoted into managerial roles with very little specific managerial training. Therefore, they tended to stick closely to procedure, as it provided a source of guidance and protected them from criticism.

This reflected a more deeply entrenched culture of risk aversion which extended beyond people management. According to one senior manager, both HR and managers were "programmed into launching straight into process" – interview 27.

At the same time, trade union representatives saw procedures as vital in protecting the interests of their members. Together, these factors resulted in relatively minor issues being channelled through the grievance procedure rather than being resolved informally.

There was an ingrained dynamic of claim and counterclaim which destroyed employment relationships and made resolution very difficult. In many, if not most, instances, the parties to conflict would "go off sick" and could "get lost in the system". Managers were often reluctant to intervene and talk to those involved as they were concerned about "getting into trouble".

One respondent reported that, at this time, it was taking an average of 60 days before cases were referred to occupational health. Resolution was extremely difficult as they had to "unravel and unpick a huge number of issues". Fundamentally, the way in which the procedure was used was a barrier to early intervention; relationships became increasingly distant and necessary conversations were less likely:

"part of the issue with the formal processes is that they take so long and in the meantime the situation gets worse, people's mental health deteriorates, and what was a small issue that might have been easy to resolve can turn into a huge big ugly monster which is much more difficult to unpick." – interview 31.

Some staff felt there was a bullying culture and that it was difficult to speak up about their problems. However, this often revolved around an absence of basic managerial practices. For example, one respondent described how the reality of her working experiences at the Trust fell far short of her expectations:

"…hearing all about the NHS, how it looked after employees, I think I had quite high expectations, which, when I came into the organisation, didn't necessarily meet my expectations…there wasn't that open culture…I never had a one-to-one, I'd never had a sit-down session with my manager to discuss how I was" – interview 16.

Others argued that managers who attempted to address personnel issues were left exposed to accusations of bullying. Furthermore, this could have negative impacts on the manager concerned and also act as a disincentive to the early resolution of problems:

"The prolonged agony for the person who is alleged to have been a bully was devastating and I think we've forgotten that. Every time someone had a poor performance against them they'd put their hands up and said they've been bullied" – interview 29.

A number of interviewees argued that bullying became a catch-all term for a very wide range of behaviours from minor relationship issues to serious instances of ill treatment. Furthermore, disciplinary cases invariably involved lengthy investigations, generally more than 6 months, and often the suspension of staff involved. This placed all staff involved under immense pressure with negative impacts on wellbeing and particularly mental health.

Although the Trust had some in-house mediation capacity, respondents suggested that this was not functioning effectively. This is particularly interesting given the fact that it had absorbed the local primary care trust, East Lancashire Primary Care Trust, in 2013.

East Lancashire Primary Care Trust had developed a successful and innovative mediation scheme, which involved training trade union representatives, HR practitioners and senior managers and also giving the trade union a substantive role in coordinating the scheme. (See also Saundry R, McArdle L and Thomas P (2011) Transforming Conflict Management in the Public Sector? Mediation, Trade Unions and Partnerships in a Primary Care Trust (PDF, 579KB)).

However, this approach was not followed by East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust and key figures from the East Lancashire Primary Care Trust scheme were excluded from involvement. Crucially, East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust's service was located within and controlled by HR, and most of the trained mediators were HR practitioners. This was seen as a problem:

"HR don't always make the best mediators. They're too process driven…they want to get in and out and provide a resolution...they want to problem solve" – interview 28.

Furthermore, mediation was simply seen as an HR process making staff "nervous" and "sceptical" of the service. More fundamentally, respondents suggested that there was a lack of real commitment to, or belief in, workplace mediation. It was argued there was a lack of mediators, and the existing ones were too busy in their day jobs to be released for mediating.

Mediation was difficult to access, and the service was slow to respond with a lead time of between 4 to 6 weeks. Moreover, mediation was generally used at the end of a process following a recommendation in a grievance or disciplinary decision. However, late intervention hampered the effectiveness of mediation at East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust:

"...you couldn't unpick 6 to 9 months of conflict. Mediation was therefore unsuccessful and developed a very poor reputation" – interview 18.

These factors combined to reduce accessibility to mediation and constrain take-up, with just 20 mediations undertaken between 2012 and 2016.

6. A new approach – early resolution

Over the last 5 years, in response to the problems outlined above, there have been 3 specific changes to the approach of East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust to the management of conflict: first, there has been renewed investment in, and commitment to, workplace mediation; second, a new Early Resolution Policy has been introduced; and third, there has been increased focus on developing managerial skills. These are now considered in turn.

6.1. Investing in workplace mediation

The development of the workplace mediation service was seen as a core element of the emerging improvement plan in the wake of the Keogh Review and negative Care Quality Commission assessments.

This involved the creation of a new full-time mediation coordinator with a specific brief to reinvigorate the scheme. This individual had previously been closely involved in the scheme at East Lancashire Primary Care Trust. Mediation was also taken out of the HR department and relocated within occupational health, emphasising the connection between dispute resolution and wellbeing rather than a narrow emphasis on cost reduction.

"there was a much stronger push towards health and wellbeing of staff and that being taken seriously, which clearly mediations fits very nicely into. So, there was a different approach, and, I guess, that probably was impacted by the change at the senior board exec level because of all the issues that had been uncovered through the special measures and the staff survey and all those kind of issues that were needed to be done to improve the organisation" – interview 31.

Moreover, it was felt that taking mediation out of HR would increase accessibility as occupational health was seen as "more impartial" and less associated with formal process.

A new cadre of mediators were also trained with candidates drawn from key stakeholder groups – trade unions, HR, occupational health and management. Furthermore, mediators were recruited from black, Asian and minority ethnic staff groups to reflect the diversity of the organisation and its community. Increasing the pool of mediators was seen as crucial in order to improve turnaround times and restore the reputation of the service.

Although there was some initial scepticism from trade unions, those union representatives that were interviewed were generally supportive of mediation as an intervention. Respondents felt that conventional processes rarely delivered positive outcomes. Mediation not only had the potential to resolve difficult issues but members with a grievance retained the option to make a formal complaint or as one respondent said "they get 2 bites of the cherry" for their members.

The speed of the mediation process compared favourably with lengthy and complex grievance procedures. This could reduce the strain on participants and help to resolve issues before they became entrenched or spread more widely within teams. Mediation provided a 'safe and calm environment' in which both parties could "say what they want". In addition, mediation gave participants greater control over the process:

"going through a formal process like HR, you have no control over that. You don't know what's going to happen at the end of it. You don't know how long it's going to take. At least, with the mediation service, you know that you're going to go into that room, it's hopefully going to be resolved on that day, and if it's not resolved, it's going to be better than it was previously. Whereas with a formal process, it can take weeks, months, you know, even years… before you've got closure" – interview 13.

Increased organisational commitment to mediation was also evident in the fact that the mediation service was provided with dedicated rooms "so I'm not fighting trying to find a room on a certain day".

In addition, each mediator was given 2 days per month to mediate, making it easier to assign mediators, and diarise mediations, improving turnaround times. Nonetheless, some respondents still found it problematic to find the time to mediate and this in turn was linked to the attitude of specific managers.

For example, one mediator reported they may get time within their working week: "[my manager] recognises it's part and parcel of being a good communicator" – interview 26. In contrast, another respondent alleged that a trained mediator in their department was often prevented from mediating for other departments:

"person in our department who's done the mediation training and the managers…are quite happy to utilise [them] and utilise [their] training. However, when [they're] asked to go to another department to actually mediate, it's quite obstructive…not allowed the time or, 'No, you have to focus on this'." – interview 21.

6.2. Early resolution – more than just an ambition?

The redevelopment of the mediation scheme provided the foundation for the second element of the Trust's conflict management strategy; the new Early Resolution Policy. This provided a potent indication of high-level support for the principle of early resolution but also directed individuals and managers towards mediation and other forms of conflict resolution and away from formal procedure.

The Early Resolution Policy essentially replaced the existing grievance, and bullying and harassment procedures; and aims to take a:

"different approach to resolving workplace issues, aligned to the Trust's values that supports an open and honest environment where workplace issues are talked through, addressed and resolved at the earliest opportunity." (East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust Early Resolution Policy ELHT HR07, version 6, page 4).

The Early Resolution Policy states:

"The purpose of this policy is to explain the Trust's response to employees who, during the course of their employment have a disagreement, conflict or complaint and ensure that they are dealt with quickly, fairly and constructively. It aims to encourage positive employee relations and to prevent bullying, harassment and any form of unacceptable behaviour between employees. The resolution policy aims to secure constructive and lasting solutions to workplace disagreements." (East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust Early Resolution Policy ELHT HR07, version 6, page 1).

This does not replace policies on disciplinary action, managing performance or attendance; however, the Trust's disciplinary policy now states that there should be a "greater focus on informal remedy…[and] where possible every effort should be made to resolve issues without using the formal procedure." (East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust disciplinary policy and procedure ELHT/HR09 version 8, page 2).

The Early Resolution Policy covers issues that are between colleagues, or staff and their manager, or impacting teams, or resources, or with the Trust itself. It advises that for Freedom To Speak Up issues such as "concern about inappropriate patient care, health and safety or fraud, bribery or corruption at work", staff should ask the Freedom To Speak Up Guardian for advice.

The policy recognises that staff may require support whilst involved in a dispute and it notes that individuals can self-refer to occupational health or the employee assistance programme, and request trade union representation. It also notes that managers can request occupational health involvement if they believe their staff require support.

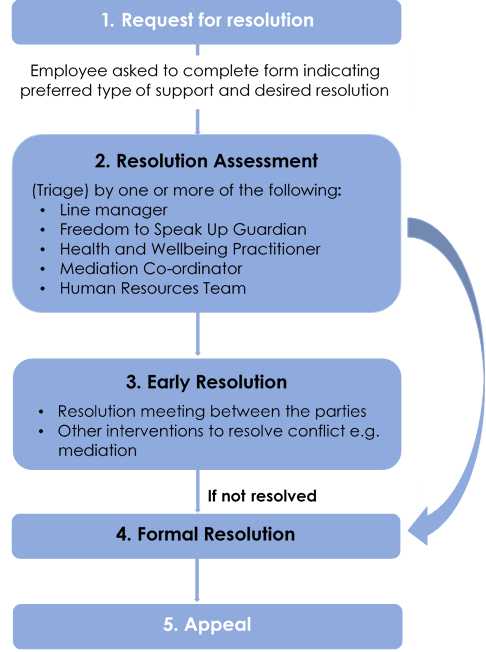

The policy does not prevent staff from making formal complaints. However, it promotes the benefits of resolution and points staff in the direction of possible sources of help. The basic process underpinning the policy is set out in figure 1, below.

If staff have a concern or complaint, they are advised to make a "request for resolution" to their line manager if appropriate. Alternatively, the staff member can choose to speak to the Freedom To Speak Up Guardian, trade union representatives, HR practitioners or occupational health or mediation coordinator, or a combination of these.

The referral is then triaged; respondents advised that staff are asked to complete a form indicating which type of support they would like, and what resolution is desired. The form is designed to provide clarity to staff and managers as to what informal resolution actually is, and what their options are before a resolution is requested.

A "resolution assessment" then takes place, in which the staff member meets with the resolution stakeholder they have requested to assess the facts of the issue and determine whether there is an agreement to proceed to early resolution. This facilitates individuals taking responsibility for the resolution of problems and triggers conversations not only between the individuals and key staff, but also between stakeholders themselves.

This in turn creates space for a wider range of interventions which can include mediation, training, coaching and facilitation, with disputants, teams or departments as required, as part of the early resolution route.

The policy states that formal resolution remains an option. For example, if an issue is deemed very serious during the "resolution assessment", it would proceed immediately to a formal procedure. In addition, if attempts at early, informal resolution are not successful, staff can request a formal resolution via a more senior manager external to the case.

However, it is important to note that referral to formal procedure is only seen as appropriate in "exceptional circumstances".

An important part of the new approach was to change the language of the policy to focus on resolving the problem rather than apportioning blame.

"it had become all very formal, into paperwork, documenting things, blame game… and then we’ve moved…we do this resolution, talking it out, a lot of it is trying to get away from formal processes" – interview 26.

For some respondents, the policy required a cultural shift, particularly for some HR practitioners and managers who were used to an approach to people management that revolved around formal policy and procedure. However, others felt that this embedded the existing direction of travel within the Trust:

"when the resolution stuff came in, we recognised we were basically already doing everything that was within this approach, but we just needed the language to mirror what we were actually doing… but it was nice to move the language from grievance to resolution" – interview 24.

HR respondents argued that the change in emphasis helped them to convince the parties in conflict to engage in more collaborative approaches. Understandably there were initial concerns from both management and unions that a greater emphasis on early, informal resolution could create additional risk and exposure to litigation:

"If you've got a process, it's really clear…if things went really badly wrong, you would want to know that a process has been followed if it ever went to a tribunal…as an organisation, you want to make sure you can demonstrate you have followed your own process and, I guess, as a staff representative, you want to know that there is a process that will keep your members safe." – interview 27.

An example of how the policy could work was given by the following respondent:

"2 people thought they were being bullied by their manager...the manager is absolutely devastated when she's found out...so rather than them putting in a formal complaint, they completed the early resolution form and they've now both been to mediation.

"I checked in with them last week and they're good to go...they're happy...so we've kept that little team together rather than 6 months of investigation." – interview 1.

Previously, this issue would have been processed through the grievance or bullying and harassment procedure with a strong likelihood that some, if not all, of those involved would have taken time off work as a result.

In another case the members of a team raised issues about the way they had been managed. They were asked to complete an early resolution form and they indicated that they would like HR, the Freedom To Speak Up Guardian and senior management to look into the issue.

The Freedom To Speak Up Guardian was asked to complete a review. Those involved were interviewed and a report was compiled identifying the problem and suggesting a potential resolution. As a result:

"they made a series of changes including identifying ‘Champions’ who staff could raise issues with, the opening of a ‘reflection room’ where people can go if they need to get away from the shop floor and there was specific training for managers…" – interview 1.

6.3. Developing managerial skills and confidence

The third element of the Trust's conflict management strategy was an increasing focus on management training. There was a recognition that many managers did not have the skills, confidence or capability to undertake conflict management.

This was partly rooted in traditional approaches to clinical recruitment and career development in the NHS, which tended to revolve around clinical and technical expertise.

However, it also reflected a view that there had been too much emphasis on leadership development which diverted attention away from the need for managers to have good basic skills:

"One of the key issues is to make sure that our managers are the best managers - that's not throwing leadership training out of the window – it’s proper management development so that they feel comfortable in their role… that's not really existed before. People would go on leadership development training and it would be all about theories of leadership but they wouldn't know how to have a conversation with someone." – interview 5.

As a consequence, the Trust developed a structured training programme – 'Engaging Managers' – which focused on the development of core people skills. There were also specific training interventions to support the Early Resolution Policy. It was recognised that it was a new approach for many managers, and they would require guidance on how to handle disputes:

"early resolution…it's hard to define…so it's hard to give people firm hand-holds and stepping stones on a training course, because there are so many variables. But what we could do at the very least is explain what the different options are and try and make them understand why it's not all set in stone. And also, let them know that, look, if they've got concerns, to contact their HR rep to talk things through, before they take action and then they can feel more confident that they're moving things in the right way" – interview 31.

However, at the time of writing, it was felt that training had not reached as many managers as needed. There were a number of reasons for this. First, the number of managers in the Trust meant that roll out of any training programme was slow.

Second, people management had to compete with an array of other training topics, many of which tended to be prioritised. Third, pressure of time meant that mandating training was challenging.

Therefore, courses were often run on a voluntary basis, which attracted managers who were more likely the ones interested in, with time and potentially already capacity for, conflict resolution. Finally, the covid pandemic halted the planned training roll out for this, and managerial development more widely:

"In terms of training for managers on the new resolution process/policy – there was some training developed which was delivered by the OD [organisational development] team and then passed over to HR ops to deliver. Part of this training did cover skills required to assist with resolving workplace conflict. We haven't delivered the training for some time due to covid." – interview 25.

Within the sample as a whole there was relatively little awareness or experience of people management training. One manager who had been on the 'engaging managers' course was still concerned that it was theoretical rather than practical, and that wider cultural changes would be required to encourage colleagues to adapt to informal resolution methods.

Another explained that they had been to a few training sessions on bullying and harassment but felt these were not very relevant and "don't really help with what we deal with" – interview 9. The focus was on the documentation and processes, rather than the interpersonal skills needed to deal with complex situations and problems:

"whereas when you're physically sat there listening to somebody...pouring their heart out to you...but we've no training, we don't know if doing the right thing or the wrong thing" – interview 9.

6.4. A strategic approach

There was general agreement from respondents that senior management were supportive of mediation and the wider push to promote early resolution. The changes in the senior management team following the Keogh Review were seen to have made a significant difference and led to people issues being pushed up the strategic agenda:

"There is a whole completely different senior management team now… we are supporting everyone, we’ve got investment in health and wellbeing, we’ve got engagement…people are being listened to now" – interview 8.

"the biggest change I've seen is probably...the senior managers seem to be getting onboard with…[and] have that kind of broader understanding of people management" – interview 24.

An examination of board-level minutes and public statements from the leadership team substantiated this view. Moreover, early resolution was linked to wider strategic goals in relation to patient care and community service. For example, the chief executive in his regular blog (January, 2019) announced the launch of the Early Resolution Policy in the following terms:

"Compassion and kindness are, of course, fundamental to the service we provide to patients and families. I am equally committed to a culture where compassion and kindness are fundamental to our leadership as well.

"We are making great progress in this area and the latest development is the launch this week of our Early Resolution Policy. This takes a more positive approach to workplace issues, promoting resolution and mediation as opposed to grievance and isolation."

Given the fact that the management of conflict is usually seen as a transactional issue and preserve of HR, such a statement is notable. Furthermore, the shift away from formal procedure reflected the new vision of the Trust adopted in the wake of the Keogh Review "to be widely recognised for providing safe, personal and effective care".

There was a clear view that the way that conflict and HR issues should be dealt with should prioritise the person rather than the process:

"We are a people business and we need to put people in front of the process. We accept there has to be a process but if that is going to cause harm then we have to consider is it fit for purpose...if you have a policy that means that the person becomes ill, you have to question...you can't be personal and go straight to a policy...so it was strategic based on the vision but there were other drivers around sickness absence, vacancy rates, waiting times...all the pressures that exist in an organisation of this size and the NHS" – interview 5.

There was also an acceptance that conflict resolution was critical in both enhancing the well-being of employees involved in such issues but also in ensuring high levels of patient care:

"What we need to do is to remove the barriers preventing someone having a better quality of life and getting back to work. If you have a surgeon who is off sick because they've fallen out with another surgeon, their list is cancelled and potentially for months patients aren't seen." – interview 5.

7. After – the impact of early resolution at the Trust

7.1 The benefits of mediation – efficiency, resolution and reflection

The use of the mediation scheme increased significantly following the overhaul of the service described above. Between September 2016 and June 2021, there were 151 individual and group mediations, 144 of which resulted in an agreement.

This is in stark comparison to the 20 mediations undertaken between 2012 and 2016. Although there was no systematic longer-term monitoring of the sustainability of agreements, the mediation service reported that they were only aware of a small number that had broken down.

It should also be noted that during covid, mediations were halted from March to July 2020, and then adapted to meet covid restrictions, which inevitably affected the use of the service. Despite the relatively high profile of mediation within some areas of the Trust, respondents felt that the scheme would benefit from greater promotion and also awareness of the differences between mediation and other forms of resolution.

There was a concern that new staff would have little understanding of the service. However, perhaps the key message was that managers needed greater buy-in so that mediation would be used at an earlier point:

"I think it's about making sure that our managers feel confident that the mediation process is there for them… that it enables a manager to express a little bit clearer what their approach has been, why they've taken that approach, potentially understand where they've maybe been clumsy or that things might have been interpreted a particular way, but at the end of the mediation, both parties are able to come away with an understanding of where they're at and agree a way forward" – interview 27.

Respondents who had taken part in mediation were generally very positive about the role played by the mediation service and the mediators themselves. Disputants reported that they received excellent support during the pre-meetings with the mediators. They were provided with information about the process and the need to be open and honest and prepared to change. One respondent explained that they had "instant rapport" with, "trusted" and "felt in safe hands" with the mediators. This reassured them that "there really wasn't anything to fear’ and they ‘felt that I could rely on [mediators] to be fair" – interview 11.

The process in the mediation room was generally described as well-structured and organised, with adequate time being given to speak. Holding mediations off-site and away from the normal working environment was seen as important in encouraging people to open up:

"We were in a completely neutral environment… not even in a building… that we normally work in, which I think was good. And the fact that you know, we each had a mediator to meet us and take us into a separate room was also good. I think I felt empowered and a lot more confident, like it wasn't anyone's sort of territory, it was completely neutral. And I felt very much supported" – interview 14.

As this suggests, neutrality and impartiality were extremely important to respondents. In the majority of cases that were examined in the research this was strictly maintained. However concerns over confidentiality were raised by 3 participants.

One respondent described that they talked to their manager about an issue in confidence which was then disclosed to the Freedom to Speak Up Guardian. Another explained that their manager had told others in the organisation about the nature and outcome of a mediation.

Respondents were generally positive about the outcomes of workplace mediation (with some reservation, which we examine in the next section). Managers that we interviewed reported that working relationships between staff in conflict typically improved:

"[The] outcome was really good because people expressed what they really felt…they saw a different side of things… it needed that honest conversation" – interview 12.

For participants, mediation could be transformational in resolving workplace problems:

"I'm so proud of myself from where I was, where I was sat at home crying, the mediation process managed to get me from sitting on the bed and not wanting to go out, to a person with a future" – interview 11.

"[Before the mediation] the member of staff that I was probably the most distant from, I'm now the most close to - we know everything about each other, we share an office, we've both supported each other massively… [we] came out of the other side… it's changed the relationship of us two…mediation has made a massive impact, positively." – interview 23.

Mediation enabled staff who were having difficulties to express their concerns honestly and find a way to work more effectively in the future:

"had we not have had mediation, had we not have had that third party, I'm not sure what would've happened, I think it would have been completely blown out of proportion, completely gone down the wrong route… not sure we'd be in the position where we are now, where we get on like a house on fire, where we've got a really good relationship… stronger than any of the others I've got with, because we've been through this experience and we've sorted it out, and I don't think we'd have got that had we not had that third party… we have such an open door policy now we just tell each other anything if we’re bugging each other" – interview 30.

Mediation was seen as a benefit to managers who might be too involved and "in the thick of" an issue. Therefore, a fresh and impartial view of a situation was seen as very valuable. Mediation helped to clarify the issues at the root of a problem, which were often longstanding and complex.

Crucially, it created an environment in which participants could reflect on the situation and the perspective of the other party. In addition, given the pressures on managers in the NHS, mediation offered vital time and space away from the workplace, which enabled resolution of issues that could not and were not being resolved in the normal busy working environment:

"…it's completely impartial, it's removed from the department, and the time period that's allocated… you are able to resolve informal issues that there would have been no chance to resolve before because you're just not able to when you're running past people in a clinical area at 100 miles an hour.

"Whereas when you can step out in silence for a couple of hours and really get into it with another member of staff, I think it has the opportunity to, kind of, resolve conflicts that would have never been resolved before" – interview 24.

Respondents identified a number of key benefits of mediation compared to conventional formal processes. Grievance procedures were slow and took up significant resources. They typically created anxiety and stress for at least one of the disputants, and long-term absence was a common consequence.

Investigations and the involvement of witnesses also had a wider impact on teams, with colleagues having to cover for absent staff and rifts emerging as sides were taken. Formal procedures tended to be conducted in a quasi-judicial manner with a focus on evidence and facts as opposed to the feelings and interests of the disputants and the underlying causes of the problem.

In contrast, mediation was generally much quicker and provided a safe, calm environment in which the parties could speak openly and understand how their behaviour was affecting others.

Perhaps not surprisingly, trained mediators were extremely positive about the role of mediation. They argued that mediation allowed participants to see the situation from the other’s perspective. Many participants did not realise the impact of their behaviour on others before the mediation, however the mediation process challenges them to reflect on their actions:

"before they go into a [mediation] room, it is a very highly pressured, stressful environment. But by the end of it, you see them totally change and there's such a release" – interview 13.

Participants were often shocked and surprised by issues raised by the other party. For several respondents, there was a moment of clarity in the mediation room when they realised the roots of the problem. For example, one respondent explained that during the mediation, they realised that they were "not without blame", as there were "things that I think I'd done that were taken [the] wrong way, that I had not realised". They argued afterwards that if mediation had happened at the start of all these issues and miscommunications, they would have been "fairly easy to rectify" – interview 21.

This points to wider impacts of mediation on the behaviour and approaches of participants. For example, a manager described how one of their team had only been prepared to seek support for personal problems after mediation as this had prompted them to reflect on how these problems were affecting their work and colleagues. The same manager also argued that mediation had a transformative impact on the other disputant who had subsequently volunteered to attend a variety of development courses and had become a "fantastic leader and coach".

Other examples included a manager adopting a coaching and mentoring approach to their department because of lessons learnt from mediation, while a group mediation prompted the adaptation of 'patient safety huddles' as a forum to speak up about staff concerns and problems, and to develop collaborative solutions.

Those trained as internal mediators also described positive benefits on their own skills and behaviours. Being a mediator highlighted the complexity of issues and the way in which misunderstandings can occur. Their experiences underlined the importance of words used, the tone in which they're expressed, body language, and appropriate approaches to use in conversations. One felt their experiences as mediator had:

"made me more empathetic… listen more, understand more, be impartial when it comes to any conflicts… think it's helped me personally" – interview 26.

7.2. Mediation – complexity and challenge

While mediation was generally seen as having a positive impact, close examination of individual cases revealed a more complex picture in which outcomes were nuanced and invariably pragmatic.

There was an acceptance that the major goal of mediation was to rescue the employment relationship so that the participants could get back to work and maintain functional relationships.

Importantly this did not mean that the staff involved had to be "friends". One respondent who felt that mediation had been "incredibly successful" also concluded that their relationship with the other party was still challenging:

"We have stuck with the agreement pretty much. I don't think our relationship is going to be anything brilliant at any point because there are still a lot of difficulties between us I think. I don't think there's some things that you're ever going to get over but we're professionals so we can definitely be professional. We can talk to each other, I can walk into a room that [they're] sat in without feeling completely sick… But we are in a better place, that has been incredibly successful." – interview 21.

A number of respondents felt that while a workable agreement had been reached, difficult relationship issues had not necessarily been fully resolved. One reason for this was the challenging nature of the mediation process which was stressful and exhausting:

"…in hindsight, I wish that I'd still had the energy towards the end of the session to, like, shape the principles of the agreement more. But at that point, I just wanted to get the hell out of there." – interview 14.

This inevitably led to some lingering concerns about the long-term sustainability of agreements reached through mediation. One respondent described that after a "honeymoon period" of a few months, the other party had reverted to some of the behaviours that had caused the conflict originally.

The relationship had become one of grudging tolerance whereby the disputants "barely spoke", although they were able to work in the same team. Respondents also had mixed experiences of the follow-up to mediations. One mediator explained that they were getting successful outcomes in the mediation room. However, they were unsure if they would hear if the agreement had broken down.

Longer-term outcomes were still often positive but did not necessarily flow directly from the mediation itself. For example, in one particularly difficult mediation, there was no agreement as the more senior manager involved was defensive and refused to engage with the process.

However, subsequently, the experience of mediation did prompt the parties to discuss their problems and consequently their relationship improved significantly. The more senior manager who had felt forced to attend was not prepared to lose face during the mediation but hearing the way in which their colleague had been affected did make them reflect on their behaviours outside the mediation.

The research also revealed that the use and timing of mediation could be inconsistent and often depended on managerial attitudes to the process. The accounts of a number of respondents suggested a danger that mediation could be used as a default process for a very wide range of people management issues.

This had the potential for cases to be referred to mediation that were inappropriate – for example where more formal disciplinary action was required or to deal with basic failures of management practice.

For example, a common agreement reached at mediation was the enforcement of people management processes, such as one-to-ones, between line managers and their direct reports.

In parts of the Trust where mediation was embedded, it was sometimes used by managers to refer issues that they should be addressing themselves. However, a lack of capability, capacity or confidence to handle conflict could make mediation an easier option. Consequently, there was a danger that seemingly simple, basic solutions could be bypassed. For example, one respondent who took part in mediation explained that while she only wanted to talk to someone, she felt pushed towards the mediation process:

"All you want is somebody to talk to… and it's got escalated and escalated to the point that I just think, 'Wow, I only wanted to talk to somebody, and I'm sat in a mediation room now. It didn't need to get to this point… I look at that now and I just think, 'Why couldn't have that happened at the start of all this?' I've gone, I've raised an issue that was impacting on, sort of, my mental health and wellbeing, that was never given as an option, it was mediation, or it was HR. I was never given that option of going and having this referral to the counselling within the trust. That was never an option, at the beginning." – interview 16.

Responses from managers themselves also reinforced that without training in conflict management they found it stressful and challenging to reach desirable resolutions; so they may refer their "troublesome staff" to mediators instead to deal with:

"takes the stress off us [managers] having to deal with troublesome staff and arguing staff… cos we're not trained… we try dealing… [with it the] best we can, but I think they’d [mediators] have a better success rate than I do. I usually end up having to move them [staff] to other sides of [the] hospital… whereas when they go to mediation I can keep them actually in the same vicinity" – interview 9.

However, where there was less managerial support for mediation, it was still used as a last resort. A number of disputants voiced regrets about not having gone to mediation sooner: one individual described the profound mental health impacts arising from the conflict they had been involved in and argued that, if mediation had happened at an earlier point, then the situation would have been "fairly easy to rectify", whereas it had escalated significantly by the time they were aware of and offered mediation:

"when I went off sick… then the manager has to start… having support meetings and involving other people, they sent me off to occupational health and I can't praise them enough, they were wonderful. Then they [occupational health] realised that maybe this relationship had just fallen apart and that other people in the team were creating more of a problem and that we needed outside help and that's when they contacted the mediation team." – interview 11.

For some managers, being asked to attend mediation with a member of their team could be seen as "punitive", "negative" and "formal" – interview 17. Some managerial respondents claimed that they had gone "through the motions" as there "seemed no other option" and were expected to attend mediation even if they were reluctant to do so.

A central tenet of mediation is that it is a voluntary process, and all parties need to be genuinely willing to go, and actively participate. However, it was acknowledged that some participants (particularly managers) may feel pressured into going into mediation. For example, one manager who agreed to go to mediation reported having felt underprepared and exposed, without a sufficient grasp of the detail of the concerns raised by the other party prior to the mediation:

"I was asked to go to mediation and I had no idea what it was about… spoke to the mediator who outlined what the concern was, and that it was that I had said something, you know, in a way, which had upset this person… we then went to the mediation… [mediators] said, 'Who wants to go first?' And I said, 'Well, as I have no idea what the meditation concern is, it's better that the colleague went." – interview 19.

7.3. Early resolution – transforming the management of conflict

There was broad support for the philosophy of the Early Resolution Policy. It was seen as a positive way of nudging managers and staff away from formal procedure and towards more creative solutions. Managers within the sample felt that the policy helped them to discuss different options with their staff and also gave them more confidence that support was available if needed:

"It is easier, I reckon, as a manager now… to deal with conflict in the workplace, knowing… these two people potentially have somewhere else to go where they can sort it out… I’ve found it more comfortable dealing with conflict now because you know that there's somewhere to go." – interview 30.

For HR practitioners, the policy had 3 potential benefits. First, it helped to explain 'informal resolution' in practical terms, something that was often unclear to managers and staff:

"I think it provides a bit of a framework and a blueprint…for the informal…actually outlining all the different options… [For HR] it's helpful because either the manager's already read it, in which case, they're already coming with an informal resolution head on. Or, when we're having to have those conversations with them… it's quite easy to say, 'Look, we've got this new policy, this is the approach… these are the mechanisms'… the employee… [beforehand] gets the grievance policy up and they see you can resolve it informally and they just think, 'I don't even know what that is.'

"Whereas now, they look at it and they can see a full page that says, 'You'll get triaged by someone impartial, you can choose who that person is, 'which is great because they're not forced to speak to anyone in particular, they've got the autonomy to make that decision of who's best for them. They've got the list of support options available, whether it be mediation, facilitated conversation, staff guardian." – interview 24.

Second, it placed a clear expectation on managers that they should use informal approaches wherever possible and appropriate. Third, it represented a cultural shift away from allocating blame and punishment towards a focus on sustainable resolution:

"What I really like about it, is the box on the resolution form which says, 'What resolution are you seeking?' Because rather than just, 'I want this person punished,' it does put the onus on them [disputant] to say this is about long-lasting, constructive solutions and what ideally would you be looking for?" – interview 24.

In terms of the impact of the policy, it is important to note that it is still relatively 'early days' in its implementation and the last 2 years have been affected by the covid pandemic. Furthermore, in the short term, it is possible that its introduction will lead to an increase in the number of issues raised as a more open culture develops.

Nonetheless, we did uncover tentative evidence that early resolution was beginning to shape the way that conflict was being managed. In total, between January 2019 and July 2022, 223 cases had been referred to informal resolution. Of these, 188 cases had been concluded (others were ongoing at the time of writing), with nearly three-quarters resolved informally and 22% progressing to formal procedure.

Furthermore, NHS staff survey results suggest that the changes discussed in this report have been accompanied by a broad improvement in people management-related indicators. There has been a decline in Trust staff stating they had 'experienced harassment, bullying or abuse at work by other colleagues in the last 12 months' from 16.9% in 2015 to 14.1% in 2021. This reduction was in contrast to the 'average' of NHS organisations the Trust has been "benchmarked" against, which increased from 17.2% in 2015 to 19.5% in 2021. (The NHS staff survey "benchmarks" each organisation against similar organisations in the NHS, to provide a comparator average score. East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust in 2021 was benchmarked against 126 Acute and Community Trusts (East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust 2021 NHS Staff Survey: Benchmark Report, page 7)).

The proportion of Trust staff reporting that they 'have personally experienced harassment, bullying or abuse at work by managers in the last 12 months' fell from 12.6% in 2015 to 8.8% in 2021. Also, in 2021, 65.3% of Trust staff stated that they "recommend my organisation as a place to work", compared to the 58.4% NHS benchmark average.

There was broad agreement among HR and trade union respondents that there had been a shift away from formal procedures and towards alternative mechanisms of resolution:

"[there has been a] reduction in sort of formal casework linked to grievances… and bullying and harassment, with the emphasis that we kind of try to resolve things and, you know, nip them in the bud and reconcile issues much sooner." – interview 28.

Furthermore, there was now more emphasis on management, HR and unions working together to try and resolve issues outside the formal process. According to one union representative:

"It was very much a case of management on one side of the table, unions on the other side of the table and never the twain shall meet, but I've found over the last 18 months or so partnership working has got a lot better. There's a lot more listening going on…" – interview 4.

One respondent felt that the organisational culture had moved from one of conflict and resistance to become "exemplary". However, while others agreed that there had been a marked improvement, the extent to which this had fed through to day-to-day management practice and staff experience varied widely depending on department and manager:

"You can tell that there has been a lot of work to improve the culture here, but I'll definitely say that it comes from the top down. So within divisions or departments I think you will find that there's a variation of experience and I think that is truly because of the manager." – interview 14.

Respondents also suggested that early resolution was beginning to have a positive impact on the confidence of line managers, helped by the relative simplicity of the process:

"It's definitely changing because [managers have] got the back-up and the support they need to address things… I think they are more confident in dealing with it but they find early resolution so useful because they have somewhere to go." – interview 1.

Furthermore, there was a sense that by making the process more accessible, serious issues that needed to be formally addressed were more likely to be uncovered. One respondent explained that a group of junior clinicians had raised a range of issues regarding the leadership style of a more senior member of staff. As part of the discussions triggered by the Early Resolution Policy, one employee had come forward with very serious allegations that were then investigated formally.