Disclaimer

This research paper was written by Rob Warren, Katie Spreadbury, Erica Garnett and Sarah Coburn at Industrial Facts and Forecasting Research.

The views in this independent research report are the authors own and do not necessarily reflect those of Acas or the Acas Council. Any errors or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the author alone. This paper is not intended as guidance from Acas nor as an endorsement by Acas of practices to be adopted in the workplace.

Foreword

I welcome this independent IFF Research report commissioned by Acas to explore the payment by employers of Acas conciliated settlements.

This study was stimulated by concerns at published research reporting worryingly high proportions of non-payment of Employment Tribunal awards. Although we had indications that employers were more likely to pay when Acas negotiated a settlement, we are extremely pleased that the evidence clearly demonstrates that this is indeed the case.

This report clearly highlights the advantages for employees of resolving their dispute with their employer through Acas, as more than 9 in 10 settlements were paid in full without the need for recourse to enforcement procedures.

Although this research covered disputes that had taken place before the introduction of early conciliation, the fact that the findings hold true for both pre-claim and post claim settlements means that settlements agreed in early conciliation are just as likely to be fulfilled.

We are pleased that the findings provide further evidence of the advantages for employers and individuals of conciliation rather than litigation.

1 Executive summary

1.1 Background and context

From April 2014 prospective claimants have been able to notify Acas of their intention to make an employment tribunal claim, (rather than submit a form directly to the employment tribunal Service), at which point Acas offers the opportunity for the employee and employer involved in the dispute to resolve the issue through a new voluntary 'early conciliation' (EC) process. In May 2014, it became a legal requirement for claimants to notify Acas for EC. However, prior to this change, from April 2009 until the introduction of EC, Acas provided a pre-claim conciliation (PCC) service in potential employment tribunal (ET) Claims. The aim of PCC was to identify disputes that were likely to become ET claims, mainly from calls to the Acas Helpline, and try to resolve them before they entered the tribunal system. Acas also has a statutory duty to provide conciliation when an employment tribunal claim has been lodged, known as individual conciliation cases (IC). The research reported upon here refers to PCC and IC cases closed between the beginning of January and end March 2014, before EC was introduced.

The aim of conciliation is to try to resolve the dispute without recourse to a full tribunal hearing. If a settlement is brokered through Acas, the conciliator draws up a legally binding document, known as a COT3, in which the terms of the settlement are recorded.

There are 2 types of settlement: those which do not require the claimant to do anything prior to the employer meeting the terms of the COT3; and conditional COT3 settlements that obliges the claimant to undertake certain actions first. Settlements may be monetary, non-monetary or a combination of the 2.

If the employer does not meet the terms of the COT3, claimants must use the County Court system in England and Wales or Sheriff Officer in Scotland to enforce the payment (claimants in England and Wales whose settlement was non-conditional may also use the 'fast track' system where, for a fee, a High Court Enforcement Officer acts on the claimant's behalf to file the claim with the county court).

There has been some concern at the proportions of claimants who have not received the awards granted to them by employment tribunals with a 2013 study estimating that only 53% of claimants had received full or part payment of their award without having to resort to enforcement and 35% had not received any money at all (Payment of tribunal awards: 2013 study). Robust evidence for payment of COT3 settlements however has not been available. Acas therefore commissioned IFF Research to undertake this study of 1,500 claimants who had settled with a COT3 agreement in both PCC and IC cases to measure levels of payment and enforcement.

1.2 Awareness of enforcement options

Prior experience and confidence with legal issues among claimants was fairly low. Just 7% of claimants had been involved in any claim or appeal to a court or tribunal before submitting the current claim to Acas for conciliation. Corresponding to this, levels of confidence with legal issues before raising the claim or dispute were fairly low, with only half of claimants saying they felt they were very or fairly confident dealing with legal issues at the time of the claim (49%).

On the whole, claimants agreed that at the time of their settlement they understood the options available to them should their employer not fulfil the settlement terms (60%). A fifth (21%) however disagreed and 15% neither agreed nor disagreed.

Almost half (46%) of claimants based in England and Wales were aware that you could enforce settlement by filing a case in the County Court directly, and just a fifth (26%) of those with a non-conditional settlement were aware of the fast track scheme as a method for enforcing payment. In Scotland just over two-fifths (44%) were aware that unpaid settlements may be enforced by a Sheriff Officer.

Of the 1,500 completed interviews, individual conciliation (IC) cases accounted for 76% of the interviews and the remaining 24% were pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases.

1.3 Profile of settlements

The majority of claims related to unfair dismissal (61%) or wages claims (13%); all jurisdictions were however represented in the sample to some degree.

Most settlements involved some form of monetary compensation; 61% were monetary only, 6% were non-monetary only and 31% had an element of both.

The mean average monetary value of the settlements was £6,600; this was however distorted by a handful of high value claims so a more representative average figure is the median at £3,000.

Over half of claimants had used a representative to deal with the case on their behalf; most commonly this was a solicitor or lawyer (63%), trade union (23%) or family member or friend (11%).

1.4 Payment of COT3 settlements, non-payment and enforcement

The vast majority (96%) of claimants who had monetary terms to their settlement had been paid in full at the time of the interview. 2% reported having been paid in part (half of which were being paid in instalments), whilst 1% had not been paid at all at the time of interviewing.

The majority of claimants (93%) who had monetary terms to their settlement received payment without needing to resort to enforcement. Overall only 4% of claimants had pursued enforcement of their settlement; of these, the majority (91% – 50 claimants) had subsequently been paid their settlement. Overall satisfaction with enforcing settlements through the County Courts was high. Whilst this only becomes important for the handful who do not receive their settlement, the high success of enforcement procedures suggests that higher awareness of the options available could lead to even higher settlement rates.

Claimants with claims known as fast track claims within Acas (for example, wages claims) were less likely than claimants with standard track (for example, unfair dismissal) claims or more complex open track (for example, discrimination) claims to have been paid in full at the time of interviewing (91% compared with 97% and 98%). Individual conciliation (IC) cases were more likely than pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases to have been paid in full at the time of interviewing (97% compared with 93%).

In order to unpick the main influences on settlement payment, a CHAID (CHi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector) analysis was conducted on the data.

Claimants who filed their claim against larger organisations were more likely to have been paid in full. The CHAID analysis allows us to identify case characteristics where settlement payment is particularly prevalent. The analysis shows us that main jurisdiction is the strongest predictor of non-payment of settlement; other important factors included income levels, size of employer and country.

The vast majority of claimants who had been paid their settlement in full (95%) reported being paid the full amount within 3 months. A further 3% reported receiving payment 3 to 6 months after the settlement and 1% over 6 months after the settlement.

A total of 13 claimants (1%) had not received any payment of the amount agreed in their settlement. Of these, 8 reported the reason they had not been paid the amount agreed was that the employer had refused to pay and 3 claimants said that the company they were claiming against no longer exists or has become insolvent.

Of the two-fifths (38%) of claimants who reported that their settlement had non-monetary terms, 7 in 10 (72%) reported that these non-monetary terms had been met in full and a further 5% reported that they had been met in part. Just 1 in 9 (11%) claimants stated that the non-monetary terms had not been met at all.

The most common reason for non-monetary terms having not been met in full (36% of claimants) was that they had not been needed yet (for example, if the settlement included the provision of a reference but the claimant has not yet required this). This is a positive finding as there is no reason to expect that these terms will not be met in full, when they are requested. However, 15% of claimants whose non-monetary terms had not been fully met said this was because the employer had refused to do so, and 7% reported it was due to delays caused by the employer. A further 5% said that the employer was unable to meet the terms of the settlement.

2 Introduction

2.1 Background and context

Employment tribunals (ET) determine disputes between employers and employees over employment rights where it has not been possible to resolve them in other ways. The types of cases that can be heard at employment tribunals cover a wide range of jurisdictions. There has been a long-term trend for an increasing number of claims made to employment tribunals which has had implications for the resource involved in running the employment tribunal system. To reduce the number of ET claims, a new early, voluntary 'early conciliation' (EC) was introduced in April 2014 where claimants notify Acas of their intention to make an Employment Tribunal claim, at which point Acas offers the opportunity for the employee and employer involved in the dispute to resolve the issue before the dispute proceeds to an ET claim. In May 2014, it became a legal requirement and all claimants now have to notify Acas of their intention to claim.

Before the introduction of EC and following an independent review of the ET system, in April 2009 Acas was given a statutory power to offer conciliation before a tribunal claim was made, in cases where an employee was eligible to submit a tribunal application and intended to do so. This pre-claim conciliation (PCC) service was the precursor of EC, and also aimed to resolve at an early stage disputes which otherwise would have resulted in a formal ET claim. This service was offered mainly to callers to the Acas Helpline. Acas also has a long-standing statutory duty to provide conciliation when an Employment Tribunal claim has been lodged, known as individual conciliation (IC) cases. The research reported upon here concerns PCC and IC cases.

Whether PCC, IC or EC, the process of conciliation is similar. Acas telephones both the parties or their representatives to ascertain whether they are willing to participate in conciliation. If both parties agree to participate in the process Acas will attempt to resolve the dispute and reach a settlement. If the dispute is resolved, Acas creates a legally binding settlement agreement (known as a COT3 after the name of the form used).

Acas conciliators will discuss the issues of the case with the parties, explain the ET process, the law and case law where appropriate, and encourage each party to consider the strengths and weaknesses of their case. They provide both parties with information on the options available to them and pass information between the parties, including details of any offers of settlement. Acas policy is that conciliators can help to clarify issues, but they do not give advice. Discussions are confidential; information given to the conciliator is not divulged to the other party without permission and what happens in conciliation cannot be used in a tribunal hearing. Settlements agreed through Acas conciliation bar access to an ET hearing.

There are 2 types of settlement: those where the terms of the agreement do not require the claimant to do anything prior to the employer meeting the terms of the agreement; and conditional COT3 settlements that oblige the claimant to undertake certain actions prior to the employer meeting the terms of the agreement. Settlements may be monetary, non-monetary or a combination of the 2, although most involve some kind of financial sum.

If the employer does not pay the agreed settlement, Acas has no powers of enforcement but can explain to the individual the relevant enforcement procedures and point out possible sources of advice. Any non-monetary element of a settlement can only be enforced through normal breach of contract action in the civil courts.

There has been some concern at the proportions of claimants who have not received the awards granted to them by employment tribunals and various studies have been carried out to explore this further. One survey carried out in 2013 estimated that only 53% of claimants had received full or part payment of their award without having to resort to enforcement and 35% had not received any money at all (Payment of tribunal awards: 2013 study).

Estimates for non-payment of COT3s have been much lower, at about 5%, but the research involved has either been qualitative (Empty justice: the non-payment of employment tribunal awards) or surveys have only included claimants who filed an ET claim, included as part of a larger Employment Tribunal claimant sample that involved all outcomes (Findings from the survey of employment tribunal applications 2013, Research Series number 177).

To gain a more accurate picture, Acas commissioned IFF Research to conduct a survey amongst a sample of claimants involved in PCC or IC conciliation where a COT3 had been issued. The sample frame also contained the track and jurisdictions for each case.

Throughout this report we refer to the employee raising the dispute in both PCC and ET claims as the 'claimant' to improve readability; it is recognised that pre-claim conciliation cases do not involve a 'claim' as such.

2.2 Methodology

The sampling frame consisted of 4,576 claimants in England, Wales and Scotland with COT3 settled IC and PCC cases that were closed in January, February and March 2014. This was the full population of claimants within this period where a COT3 settlement had been issued. This yielded 3,608 records with usable contact details which were drawn as sample for the survey.

All those in the starting sample were sent an introductory letter about the survey. This was to provide reassurances about discussing their experiences, which have the potential to be quite sensitive, and also provided them with the opportunity to opt out of the survey.

A total of 1,500 interviews were achieved from this sample between 20 August and 24 September 2014. Of these interviews, 1,360 were completed with claimants who went through the COT3 settlement process in England and Wales and the remaining 140 with claimants who went through the COT3 settlement process in Scotland.

Acas categorises cases as 'fast', 'standard' or 'open' track depending on the jurisdictions involved. Fast track cases are straightforward claims that concern mostly breaches of contract or monetary disputes, for example unauthorised deductions from wages; standard track cases are more complex cases mostly involving claims of unfair dismissal and open track cases are the most complex discrimination cases. In general, PCC attracts more fast track cases and fewer open track cases than IC.

Individual conciliation (IC) cases accounted for 1,135 of the interviews and the remaining 365 were pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases. IC cases were most commonly standard track (47%) closely followed by open track (44%). A minority were fast track (9%). PCC cases were most commonly standard track (46%) and fast track (40%). A minority were open track (13%).

Interviews were conducted by telephone using Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) technology and lasted approximately 15 minutes on average.

The survey questionnaire was developed in close collaboration with Acas and was based upon the questionnaire IFF had developed for the BIS Payment of Tribunal Awards survey in 2013 (Payment of tribunal awards: 2013 study). Following a discussion of amends to that questionnaire, IFF produced a new draft questionnaire for review by Acas. Upon receipt of comments on the draft, IFF worked closely with Acas to refine the questionnaire in an iterative way, responding to comments and providing input on question ordering and wording (including style and tone), usefulness of questions (i.e. whether or not it would be possible to undertake meaningful analysis of the responses) and questionnaire length.

Overall a response rate of 77% was achieved, calculated as a proportion of all completed contacts (completes or completes and refusals). Table 2.1 shows the full breakdown of usable sample.

| Number | % of sample | % of completed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total usable sample | 3,608 | 100% | — |

| Unobtainable number | 389 | 11% | — |

| Ineligible (had not agreed settlement with Acas, conditions of conditional settlement not met, business number) | 214 | 6% | — |

| Unresolved (no answer, engaged) | 1,063 | 29% | — |

| Total complete contacts | 1,942 | 54% | 100% |

| Interview terminated by claimant | 98 | 3% | 5% |

| Claimant refused | 344 | 10% | 18% |

| Completed interview | 1,500 | 42% | 77% |

To correct for slight variations in the response rate by jurisdiction, a non-response weight was applied at the analysis stage to ensure the spread of the main jurisdiction in the data analysed matched that of the population. Table 2.2 below shows the impact of this weighting.

| Unweighted n | Unweighted % | Weighted n | Weighted % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfair dismissal | 929 | 62 | 914 | 61 |

| Wages claims | 202 | 13 | 197 | 13 |

| Sex discrimination and equal pay | 66 | 4 | 78 | 5 |

| Breach of contract | 106 | 7 | 101 | 7 |

| Disability | 97 | 6 | 96 | 6 |

| Other (grouped responses not high enough to analyse individually) | 100 | 7 | 114 | 8 |

2.3 Data treatment

Responses to each question were compared and any differences tested for statistical significance. Throughout this report where differences are noted between sub-groups, they are statistically significant at the 95% level (unless otherwise stipulated).

Throughout the report when the number of claimants is given as a figure rather than a percentage this refers to the number within the sample rather than the population figure.

In order to unpick the main influences on payment of settlement, a CHAID (CHi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector) analysis was conducted on the data. This is a form of analysis that identifies variables that have the strongest interactions to maximise the extent to which the dependent variable (in this case payment of settlement as detailed in COT3) can be explained. The outputs of this are reported in chapter 5, and a full explanation of the CHAID model in Annex A.

2.4 About this report

The report is structured as follows:

Chapter 3: Profile of claimants

This chapter provides an overview of the COT3 settlement population, including their demographics, working status before and after making the claim, relationship with the employer involved in the dispute and their confidence in dealing with legal issues and prior awareness of enforcement options.

Chapter 4: Nature of the settlement

This chapter builds on the previous one by looking at the nature of the claims covered by the survey. This includes the type of employer, jurisdictions, value of the settlement and the details of the case such as the time it took and whether legal help was used.

Chapter 5: Payment of settlement, reason for non-payment and enforcement

This key chapter covers whether the COT3 settlement has been paid in full or in part, and by whom. This is broken down by payment received before and after the effects of enforcement, allowing analysis of those who received their settlement without enforcement as well as payment at an overall level. It looks at factors that help predict which settlements will and will not be paid. Chapter 5 also looks at timelines of payment, and where settlements have not been received it looks at reasons for this.

Profile of claimants

This chapter outlines the demographic profile of claimants who reached a COT3 agreement brokered through Acas.

3 Profile of claimants

This chapter outlines the demographic profile of claimants who reached a COT3 agreement brokered through Acas.

3.1 Demographics

As shown in Table 3.1 the gender profile of claimants is fairly evenly split although there were slightly more males than females (53% compared to 47% respectively).

The vast majority (86%) were aged 30 or over. Most commonly claimants were aged 35 to 44 (35%) or 45 to 54 (29%) although a sizeable minority were aged 55+ (22%).

Table 3.1 also shows that almost half (49%) were married and a further 14% were cohabiting or living with a partner. Around one quarter (25%) were single and a small proportion was either separated or divorced (8%) or widowed (1%).

The vast majority (83%) did not consider themselves to have a disability.

A higher proportion of claimants were in the social grades ABC1 (59%) with 39% falling into the social grades C2DE.

The majority of claimants spoke English as their first language (88%).

Tables 3.1 Gender, age, marital status, disability, social grade of claimants

| Gender | All claimants | PCC | IC | SETA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 53% | 55% | 52% | 57% |

| Female | 47% | 45% | 48% | 43% |

| Age | All claimants | PCC | IC | SETA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under 30 | 14% | 24% | 11% | 47% |

| 30 to 44 | 35% | 39% | 34% | 47% |

| 45 to 54 | 29% | 21% | 31% | 29% |

| 55+34 | 22% | 17% | 23% | 23% |

| Marital status | All claimants | PCC | IC | SETA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married or civil partner | 49% | 45% | 50% | 48% |

| Single | 25% | 31% | 24% | 38% |

| Cohabiting or living with a partner | 14% | 14% | 14% | 38% |

| Separated or divorced | 8% | 6% | 9% | 11% |

| Widowed | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Disability | All claimants | PCC | IC | SETA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has a disability | 16% | 12% | 18% | 19% |

| Does not have a disability | 83% | 87% | 82% | 81% |

| Social grade | All claimants | PCC | IC | SETA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABC1 | 59% | 53% | 60% | n/a |

| C2DE | 39% | 44% | 38% | n/a |

| Ethnicity | All claimants | PCC | IC | SETA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 77% | 79% | 77% | 82% |

| Mixed | 2% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Asian or Asian British | 6% | 5% | 7% | 5% |

| Black or Black British | 6% | 6% | 6% | 7% |

| Other | 8% | 8% | 8% | 1% |

3.2 Work status and income

Employment levels were higher among claimants before contact was made with Acas (81% were employed then compared to 66% at the time of the interview). This difference is particularly marked in the full-time work category (66% of claimants were in full-time work before they contacted Acas compared to 49% at the time of the interview).

Almost three-quarters (72%) of claimants who were in work before they contacted Acas about their dispute were still in work at the time of the interview (51% in full-time work, 17% in part-time work and 4% in self-employment). Of the remaining, 15% were unemployed, 4% were not working because of sickness or disability, 4% were retired, 2% were looking after the home or family and 2% were in education or training.

A third of claimants (33%) were working for the employer involved in the dispute at the time of contacting Acas and 66% had worked for them previously but were no longer doing so when they contacted Acas. Just 1% had not worked for the employer involved in the dispute at all, for example, in cases where the dispute was related to a job application.

At the time of the interview the majority of claimants had been working for the employer for more than 1 year; just under half (49%) had worked for them for over 5 years, 36% for between 1 and 5 years and 14% for up to 1 year.

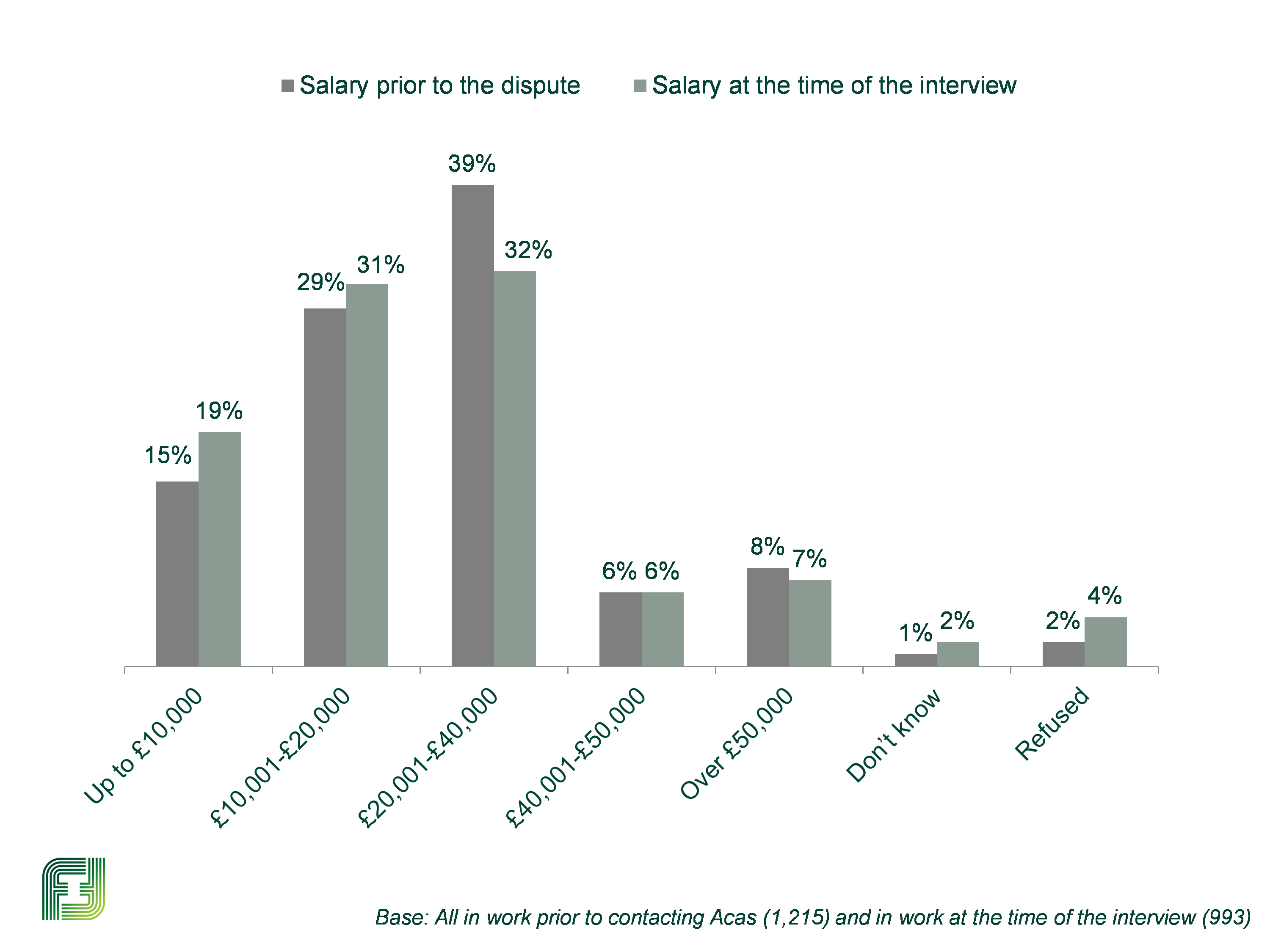

As shown in Figure 3.1, there was some variation in claimant salary between the time of the interview and the time prior to the contact with Acas; slightly more were earning £10,000 or less (19% compared to 15% prior to contacting Acas) and slightly fewer were earning in the salary band £20,001 to £40,000 (32% compared to 39% prior to contacting Acas).

Generally speaking, the proportion of claimants in the higher salary bands (£20,000+) had decreased, and the proportion in the lower salary bands had increased. While around three-fifths (57%) of claimants in work at the time of the interview were earning in the same band pre and post contacting Acas, 12% were earning more and almost one quarter (23%) were earning less. This demonstrates the impact of the incidents leading to the claim.

3.3 Job role

As shown in Table 3.2, the occupational profile of claimants at the company at which a dispute was raised was fairly evenly spread although there were slightly more in manager or senior official roles (17%) and associate professional or technical roles (18%).

| Job role | All claimants who worked for company they made a claim against (1,483) |

|---|---|

| Manager or senior officials | 17% |

| Professional | 9% |

| Associate professional or technical | 18% |

| Administrative or secretarial | 10% |

| Skilled trades | 10% |

| Personal service | 8% |

| Sales and customer service | 8% |

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 9% |

| Elementary | 10% |

3.4 The organisation involved in the dispute

Almost one-half (48%) of disputes were with large companies (employing 250 or more staff) while similar proportions of micro, small and medium companies were involved in a dispute (12%, 17% and 15% respectively).

The vast majority of disputes were in the private sector (80%) with 14% in the public sector and just 5% in the charity or not for profit sector.

3.5 Confidence with legal issues

Just 7% of claimants had been involved in any claim or appeal to a court or tribunal before submitting the current claim to Acas for conciliation. However, levels of confidence with legal issues before raising the claim or dispute were fairly evenly mixed with around half of claimants saying they felt they were very or fairly confident dealing with legal issues at the time of the claim (49%), 40% saying they were not confident and 11% that they were neither confident nor unconfident.

Those claiming against public sector companies were most likely to say that they were not confident in dealing with legal issues before their claim or dispute (46% compared to 40% average). This is significantly higher than those claiming against a charity or not for profit organisation (27%) but not significantly different from those claiming against private sector companies (39%).

Confidence in legal matters also depended on the job role of claimants prior to the dispute with 52% of those in manager, professional or associate professional roles and in administrative or skilled trades roles saying they were confident compared to 42% of those in caring, leisure, sales or service roles and in operative or elementary roles.

Age and gender impacted on claimant confidence with those aged 45 to 54 and 55 and over more confident than those aged under 30 (51% and 55% compared to 39%) and males more confident than females (52% compared to 45% respectively). There was little variation by ethnicity.

In terms of the case jurisdiction, those claiming for breach of contract were more confident (58% compared to 48% on average) while those claiming under the disability jurisdiction were less confident (37% compared to 49% not claiming under this jurisdiction).

3.6 Awareness and understanding of enforcement options

The Acas letter accompanying the COT3 states that:

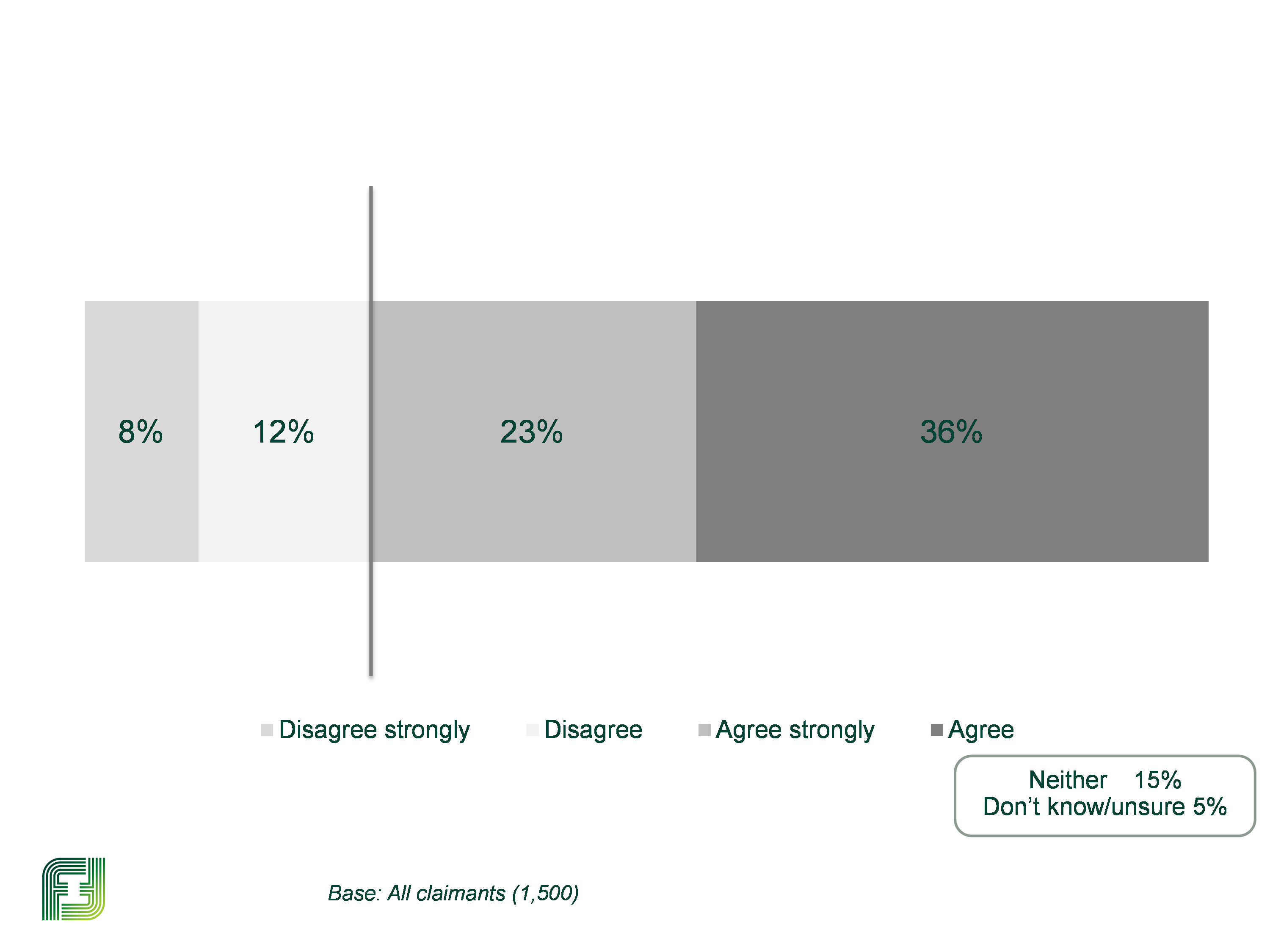

On the whole, claimants agreed that at the time of their settlement they understood the options available to them should their employer not fulfil the settlement terms (60%). However, a fifth (21%) disagreed and 15% neither agreed nor disagreed. Figure 3.2 illustrates the findings.

Claimants with fast track claims were more likely than claimants with standard track or open track claims to agree that they understood the options that were available to them (71% compared with 60% and 54%). Claimants with standard track claims were also significantly more likely than those with open track claims to agree.

Pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases were more likely than individual conciliation (IC) cases to agree that they understood the options that were available to them (65% compared with 58%).

Male claimants were more likely than female claimants to agree they understood (63% compared with 56%).

Claimants that did not pursue enforcement of their settlement payment were asked if they were aware of each of the specific ways of trying to enforce payment that were available to them. The County Court is available to all claimants in England and Wales, whereas fast track is only available to claimants in England and Wales who have a non-conditional settlement. The Sheriff Officer is available to all claimants in Scotland.

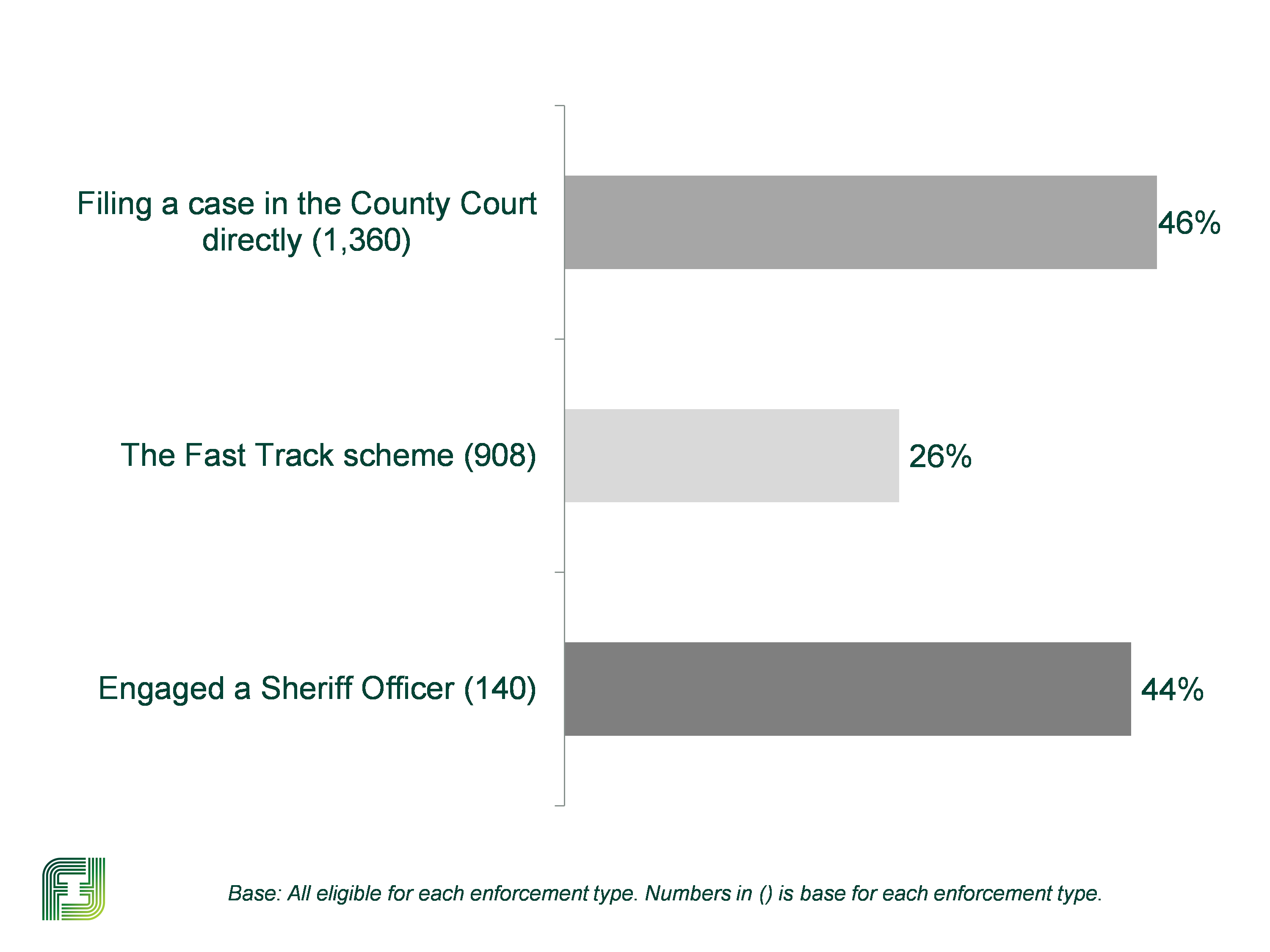

As shown in Figure 3.3, almost half (46%) of claimants based in England and Wales were aware that you could enforce a settlement by filing a case in the County Court directly. A fifth (26%) of those with a non-conditional settlement were aware of the fast track scheme as a method for enforcing payment.

Just over two-fifths (44%) of claimants based in Scotland were aware that unpaid settlements may be enforced by a sheriff officer if they have a copy of the COT3 which sets out how much the employer must pay.

Finally, in relation to enforcement, only 2% of claimants had sought any advice about enforcing their settlement from any organisation or person. Of the 12 claimants who had not been paid at all a third had sought advice about enforcing their settlement from any organisation or person (due to the low base size we have not reported percentages).

Whilst this only becomes important for the handful who do not receive their settlement, the high success of enforcement procedures suggests that higher awareness of the options available could lead to even higher payment settlement rates.

4 Nature of the settlement

This chapter looks at the types of disputes; the jurisdiction, the value of the settlement agreed upon and the non-monetary terms of the settlement.

This chapter will also look at whether claimants had a representative at any stage in the process and at their level of confidence in dealing with legal matters prior to making the claim.

4.1 Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction for each case was taken from the records supplied by Acas.

The majority of disputes related to unfair dismissal (61%) while the remaining cases fell under the jurisdiction of wages claims (13%), breach of contract (7%), disability (6%) and sex discrimination and equal pay (5%). The remaining 8% were involved one of a number of different jurisdictions such as discrimination on the grounds of age, race or religion. Section 4.2 looks at unfair dismissal and wages disputes in further detail as these were the most common types of jurisdiction.

4.2 Unfair dismissal and wages disputes

Patterns evident in the types of companies, persons and cases involved in unfair dismissal disputes are generally the opposite of those found in the companies, persons and cases involved in wages disputes.

Unfair dismissal cases were more commonly individual conciliation (IC) cases (67% compared to 42% of pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases) while disputes about wages were more commonly PCC cases (34% compared to 6% of IC cases).

As shown in Table 4.1, unfair dismissal disputes were most common in larger companies, while disputes relating to wages tended to be made against smaller companies.

| Micro (1 to 9) | Small (10 to 49) | Medium (50 to 249) | Large (250+) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: | (170) | (243) | (210) | (658) |

| Unfair dismissal | 48% | 50% | 71 | 65 |

| Wages claim | 22% | 22% | 12 | 9 |

In line with the average distribution of tenure (the majority of claimants were more established at their company; just under half (49%) had worked for them for over 5 years, 26% for between 2 and 5 years and 25% for up to 2 years), those claiming unfair dismissal tended to be more established at the company they were in dispute with. Those making a wages claim were less established.

Longer standing employees

Longer standing employees were more likely to claim unfair dismissal (31% of those who had been at the company for up to 1 year compared to 68% of those who had been at the company for 2 to 5 years and 73% of those who had been there for over 5 years).

Those making a wages claim

In contrast, those making a wages claim had generally been at the company for less time (30% of those who had been at the company for up to one year made this type of claim compared to 11% of those who had been at the company for between 2 and 5 years and 6% of those had been there for over 5 years).

Impact of level of earnings

The tendency to make a claim for unfair dismissal increased with claimant level of earnings prior to contact with Acas (53% of those earning up to £20,000, 65% of those earning £20,001 to £40,000 and 65% of those earning over £40,000 made a claim for unfair dismissal) while those earning a salary in the smallest band (up to £20,000) were slightly more likely to make a wages claim (18% compared to 13% average).

Part time employees

Those who had worked for the company on a part-time basis were less likely to claim for unfair dismissal (52% compared to 62% of full-time staff) and more likely to make a wages claim (21% compared to 12% of full-time staff).

As shown in Table 4.2, claimant age also had a different impact on the 2 jurisdiction groups; the proportion of those claiming for unfair dismissal increased with age while the proportion of those making a wages claim decreased with age. This is linked to tenure which increases with age; for example, those aged under 30 were more likely to have worked for the employer for less than a year (34% compared to 14% average) and those aged 55 and over were more likely to have worked for the employer for over 10 years (44% compared to 27% average).

A third of claimants with a disability were claiming about disability discrimination (32%), however for two-thirds of claimants with a disability the main jurisdiction of their claim was not disability discrimination.

The 2 jurisdictions also tended to involve different types of cases; unfair dismissal cases were more commonly individual conciliation (IC) cases (67% compared to 42% of pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases) while disputes about wages were more commonly PCC cases (34% compared to 6% of IC cases).

| Under 30 | Aged 30 to 44 | Aged 45 to 54 | Aged 55 and over | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: unweighted | (212) | (530) | (430) | (324) |

| Unfair dismissal | 42% | 58% | 68% | 70% |

| Wages claim | 26% | 15% | 9% | 6% |

4.3 Settlement amount and terms

Most settlements involved some form of monetary compensation; 61% were monetary only, 6% were non-monetary only and 31% had an element of both.

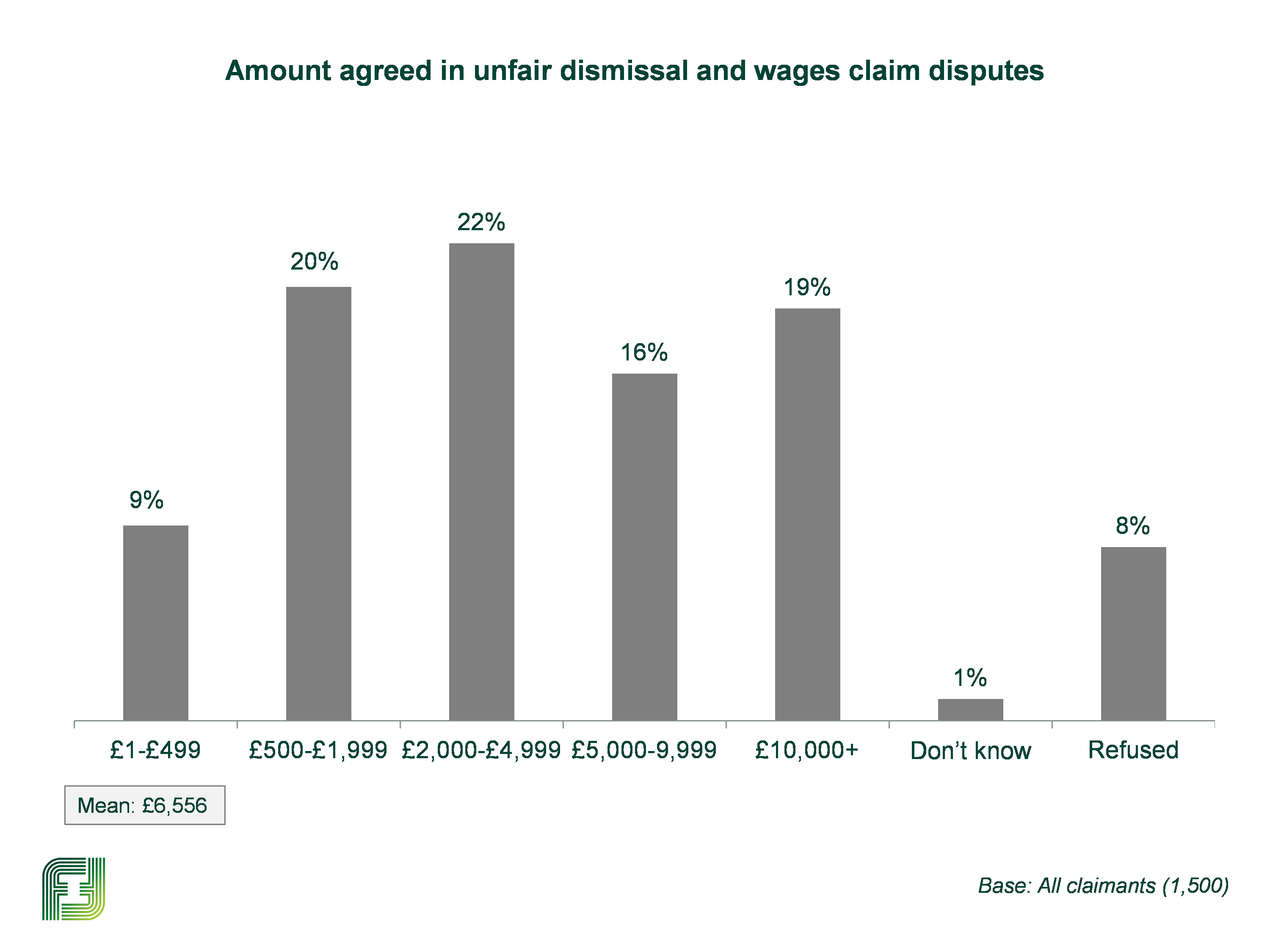

As shown in Figure 4.1, the mean average value of monetary settlements was £6,600; this was however distorted by a handful of high value claims so a more representative average figure is the median at £3,000. The proportions in each settlement band are fairly similar although much fewer settlements fell into the band of £1 to £499 pounds (9%) and slightly fewer into the band of £5,000 to £9,999 (16%).

As one would expect there is considerable variation in the value of the settlement when looking at the amount by jurisdiction. As shown in Table 4.3 below, claims of unfair dismissal, sex discrimination and equal pay and of disability tended to reach a higher settlement while wages claims and breach of contract tended to reach a lower value settlement.

| Unfair dismissal | Wages claim | Sex discrimination and equal pay | Breach of contract | Disability | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: unweighted | (929) | (202) | (66) | (106) | (97) | (100) |

| £1 to £499 | 3% | 37% | 2% | 14% | 1% | 8% |

| £500 to £1,999 | 16% | 29% | 13% | 39% | 15% | 26% |

| £2,000 to £4,999 | 24% | 16% | 32% | 19% | 22% | 19% |

| £5,999 to £9,999 | 19% | 7% | 18% | 9% | 17% | 14% |

| £10,000 or more | 23% | 4% | 28% | 8% | 18% | 19% |

| Mean | £7,320 | £3,110 | £9,690 | £3,650 | £7,630 | £6,360 |

| Median | £4,360 | £830 | £5,500 | £1,590 | £4,000 | £3,000 |

Note: Mean and median rounded to nearest £10

Looking at company type, micro companies tended to be involved in lower value claims (8% incurring claims of £10,000 or more compared to 17% of small companies, 20% of medium companies and 22% of large companies). Public sector companies (involved in 14% of all claims) were most frequently involved in settlements requiring payment of over £10,000 (28% compared to 19% average and 17% of private sector companies).

The amount of the settlement also depended on how established or senior claimants were at the company against which they had made their claim; this is likely to be linked to their salary before the claim. Specifically, the likelihood of agreeing a settlement of £10,000 or more increased with the seniority of the job role, claimant income, length of tenure and working hours.

Manager or senior professional

Those in manager or senior professional roles were more likely than those in administrative and skilled trade roles to have agreed a settlement of £10,000 or more (26% compared to 18%) while those in administrative and skilled trade roles were more likely than those in caring, leisure, sales or service roles and those in operative or elementary roles (18% compared to 10% and 11% respectively).

Employed over 5 years

Those who had been at the company for over 5 years were more likely to have agreed a settlement of £10,000 or more than those who had been at the company for 2 to 5 years who were in turn more likely than those who had been at the company for up to one year (25% compared to 16% compared to 6%).

Working full-time

Those working full-time were more likely to reach a settlement of £10,000 or more than those working part-time (21% compared to 10%).

Those earning more than the average of claimants sampled

Those earning more than the average of claimants sampled were more likely to reach a settlement of £10,000 or more than those earning less; 48% of those earning over £40,000 compared to 23% of those earning £20,000 to £40,000 and both of these compared to 7% of those earning up to £20,000.

Patterns are also evident when looking at settlement value by claimant age, language and social grade.

Aged under 30

6% of those aged under 30 agreed a settlement of £10,000 or more compared to 17% of those aged 30 to 44, 23% of those aged 45 to 54 and 26% of those aged 55 or over.

Speak English as a first language

20% of those who spoke English as a first language agreed a settlement of £10,000 or more compared to 12% who did not.

In social grade ABC1

23% of those in social grade ABC1 agreed a settlement of £10,000 or more compared to 14%% of those in C2DE.

Finally, type of case played a part in the level of the settlement. Open track discrimination cases were most likely to result in settlements of £10,000 or above (27% compared to 19% of standard track cases and 3% of fast track cases). IC cases were more likely to result in settlements of £10,000 or more than PCC cases (22% and 9% respectively).

4.4 Non-monetary terms or conditions of the settlement

37% of claimants agreed upon non-monetary terms as part of their settlement. The majority of these (83%) also included a financial sum. Such claimants were asked to outline what these non-monetary terms were.

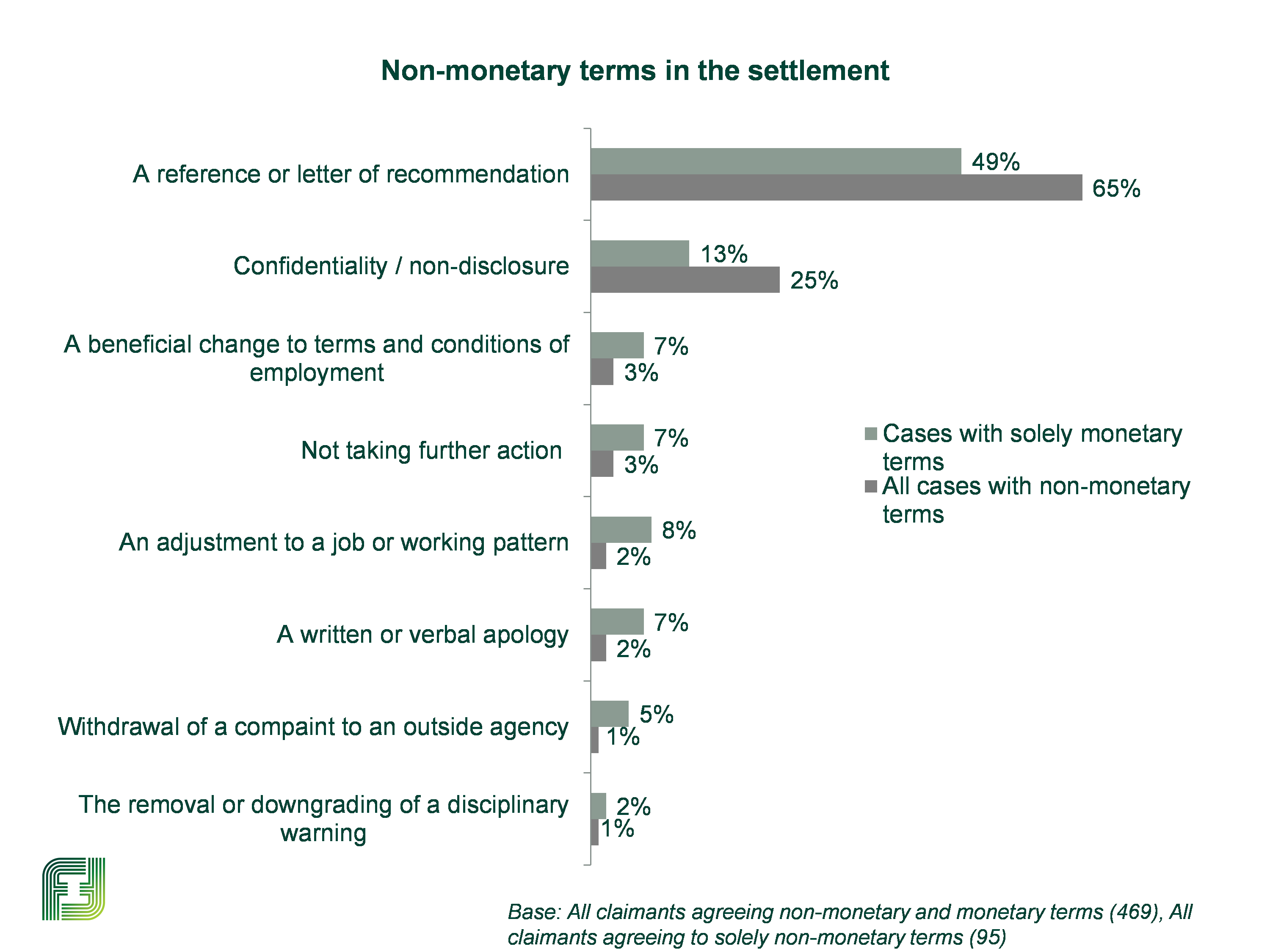

As shown in Figure 4.2, among all those with non-monetary terms in their agreement, the vast majority included a reference or letter of recommendation (65%). 25% also said that their settlement contained a confidentiality or non-disclosure clause. These were also the most common terms or conditions mentioned among those whose agreement was solely non-monetary (49% mentioned a reference or letter of recommendation and 13% mentioned a confidentiality or non-disclosure agreement). Other terms or conditions cited by claimants were: request for an adjustment to working terms or conditions (7%), a commitment to not take further action (7%), an adjustment to a job or working pattern (8%) and a written or verbal apology (7%).

The request for a reference or letter of recommendation was most common for cases involving charities or not for profit organisations (82% compared to 66% of private sector companies and 56% of public sector companies) and those who had worked for the company on a full-time basis (66% compared to 53% who had worked for the company on a part-time basis).

Agreements involving the highest value settlements (£10,000 or over) most frequently included a request for a reference or letter of recommendation (77% compared to 65% on average) as did unfair dismissal claims (70% compared to 55% of other types of claims) reflected in the fact that more standard track cases (72% compared to 63% of open cases and 28% of fast track cases) included this request.

4.5 Use of claimant representatives

Over half (56%) of claimants had a representative who dealt with the dispute on their behalf. This was commonly a solicitor or lawyer (63%) a trade union (22%) or a family member or friend (11%).

Those involved in IC cases were more likely to have used a representative (67% compared to 22% of PCC cases).

Those claiming against micro companies were the least likely to have had turned to a representative during their claim or dispute (46% compared to 56% of medium companies and 60% of large companies). These proportions of micro and large employers are significantly different to the average (56%).

Those claiming against public sector companies were the most likely to have consulted a representative (69% compared to 55% of private sector companies and 47% of charities or not for profit organisations).

There was an association between having a representative and the value of the settlement. Just 23% of employees whose settlement was worth under £500 had a representative to deal with the claim on their behalf, rising to 74% of claimants whose settlement was worth £10,000 or more. Similarly, those earning a higher income prior to contacting Acas were more likely to seek help from a representative, as were those who had been working at the company for longer.

Claimants whose settlement was worth over £2,000 were more likely to use a solicitor or lawyer for this support (69% compared to 42% of those whose settlement was worth less than £2,000). Claimants whose settlement was worth less than £2,000 were more likely than those whose settlements were worth more to use a friend or family member (19%, compared to 8%), or a Trade Union (26%, compared with 20%).

Claimant age, gender and disability also impacted on whether or not claimants sought help from a representative:

a) older claimants more likely to seek help from a representative (61% of those aged 55 or over and 61% of those aged 45 to 54 compared to 53% of those aged 30 to 44 and 48% of those aged under 30)

b) those reporting a disability more likely than those who did not (62% and 55% respectively)

c) women more likely than men (59% and 54% respectively)

Looking by case type, claimants involved in fast track conciliation, such as wages claims, sought support less frequently than those who were involved in standard (for example unfair dismissal) or open track discrimination cases (33% compared to 55% and 68% respectively).

5 Payment of settlement, reasons for non-payment and enforcement

This chapter explores fulfilment of claimants' settlement as detailed within their COT3. The chapter will discuss at an overall level whether the settlement had been paid in full, in part or not at all and whether enforcement was used to attempt to obtain payment at the time of interviewing. Any sub-group differences in regards to payment or non-payment will also be discussed. The chapter also details the timelines for receiving payment, fulfilment of any non-monetary terms of the settlement and perceived reasons for non-payment and or fulfilment of the non-monetary terms.

5.1 Payment of monetary settlements overall

The vast majority (96%) of claimants who had monetary terms included in their settlement had been paid in full at the time of the interview. 2% reported having been paid in part, whilst 1% had not been paid at all at the time of interviewing. A further 1% were unsure or refused to confirm whether their settlement had been paid in full. As mentioned in the background and context chapter, cases that were closed in January, February and March 2014 were included within the research. Therefore between 5 and 7 months had elapsed between the cases being closed and the interviewing period. The proportion of claimants reporting being paid their settlement could go up further as some employers may take longer than this to settle the settlement.

Of the 2% who had been paid in part, approaching half said this was because they were being paid in instalments (and would therefore expect to receive full payment in time).

5.2 Differences in payment outcome

All cases with monetary terms to their settlement where the main jurisdiction of the claim was 'sex discrimination and equal pay' or 'disability discrimination' had been paid in full at the time of interviewing (100% for both). The main jurisdiction that was least likely to result in payment in full was breach of contract; however the vast majority (91%) had still been paid in full. Payment by main jurisdiction is shown in Table 5.1.

| Unfair dismissal | Wages claim | Sex discrimination and equal pay | Breach of contract | Disability | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: unweighted | (868) | (196) | (63) | (100) | (84) | (93) |

| Paid in full | 97% | 94% | 100% | 91% | 100% | 95% |

| Paid in part | 1% | 4% | — | 6% | — | 3% |

| Not been paid | 1% | 2% | — | 2% | — | 2% |

| DK or refused | 1% | 1% | — | 1% | — | — |

Base: All claimants. '-' denotes zero

The value of the settlement impacted upon the likelihood of it being paid in full. As shown in Table 5.2 those who were claiming an amount of £1 to £499 were least likely to have been paid in full and most likely to not have been paid at all at this stage. As might be expected, claimants with the highest claim value (£10,000+) were most likely to respond that they had been paid in part, albeit still a low proportion (4%).

| £1 to £499 | £500 to £1,999 | £2,000 to £4,999 | £5,000 to £9,999 | £10,000+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: unweighted | (131) | (298) | (333) | (240) | (284) |

| Paid in full | 93% | 98% | 98% | 99% | 96% |

| Paid in part | 3% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 4% |

| Not been paid | 3% | 1% | 1% | * | — |

| DK or refused | 1% | — | — | — | — |

Base: All claimants. '-'denotes zero, '*' denotes a figure greater than zero but less than 0.5

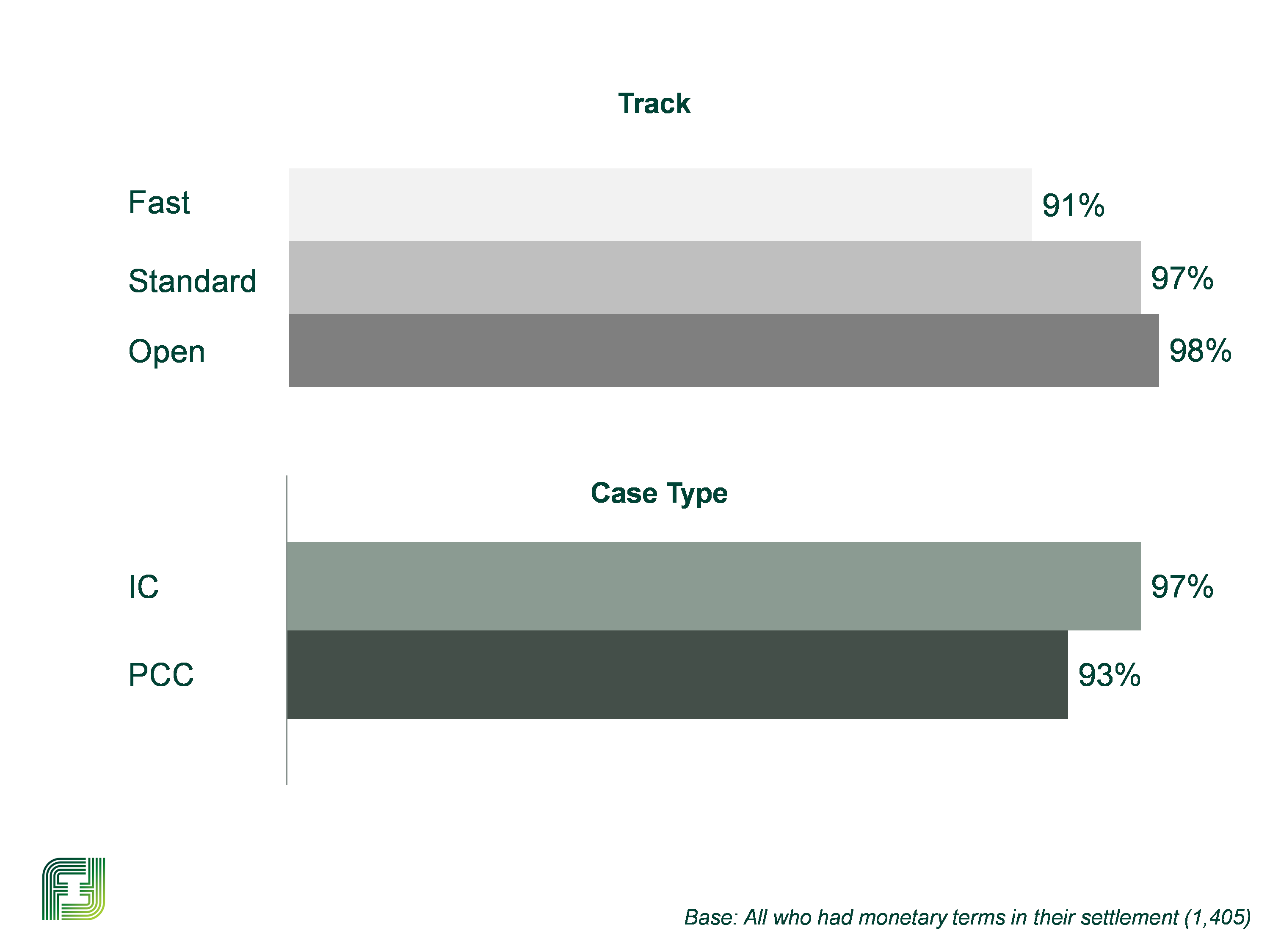

Figure 5.1 displays the proportions being paid in full by both track and case type. Claimants with fast track claims, for example wages claims, were less likely than claimants with standard track claims (for example unfair dismissal) or open track discrimination claims, to have been paid in full at the time of interviewing (91% compared with 97% and 98%).

Individual conciliations (IC) were more likely to be standard or open track cases (47% and 44% compared to 9% fast track), both of which, as mentioned, were more likely than fast track cases to have been paid in full. This might explain why IC cases were more likely than pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases to have been paid in full at the time of interviewing (97% compared with 93%).

Claimants who filed their claim against larger organisations were more likely to have been paid in full. As shown in Table 5.3, claims against large employers and medium employers were significantly more likely to have been paid in full (98% for both) than claims against micro (95%) or small employers (91%).

Those who had only been paid in part were less likely to have used a representative (30%, or 8 claimants, compared to 56% average). These results should be interpreted with caution due to the low base size; only 27 claimants were paid in part.

| Micro (1 to 9) | Small (10 to 49) | Medium (50 to 249) | Large (250+) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base: | (170) | (243) | (210) | (658) |

| Paid in full | 95% | 91% | 98% | 98% |

| Paid in part | 4% | 6% | — | * |

| Not been paid | 1% | 1% | 2% | * |

| DK or refused | 1% | 2% | — | 1% |

Base: All claimants. '-' denotes zero, '*' denotes a figure greater than zero but less than 0.5

All claimants with a disability who had monetary terms to their settlement had been paid in full at the time of interviewing compared with 96% of those without a disability.

5.3 Payment outcome by time elapsed from settlement

Four-fifths (78%) of those whose settlement had been paid in full, and who recalled how soon after the settlement the settlement was paid (i.e. excluding those who responded 'don't know'), were paid the full amount within one month of the settlement. A further 17% reported being paid within one month to 3 months of the settlement. Therefore, the vast majority (95%) reported being paid the full amount of their settlement within 3 months. A further 3% reported receiving payment 3 to 6 months after the settlement and 1% over 6 months after the settlement. Those who were paid in full without resorting to enforcement were more likely to report being paid the full amount of their settlement within 3 months than those who resorted to enforcement (96% compared with 89%).

Smaller employers, on average, took longer to pay the settlement; 89% of claimants claiming against an employer with 1 to 9 employees had been paid in full within 3 months of the settlement, compared with 95% of those with 10 to 49 employees, 97% of those with 50 to 249 employees and 97% with 250 or more employees.

5.4 Relative importance of factors affecting settlement payment

In order to unpick the main influences on settlement payment, a CHAID (CHi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector) analysis was conducted on the data. This is a form of analysis that identifies variables that have the strongest interactions to maximise the extent to which the dependent variable (in this case payment of settlement as detailed in COT3) can be explained.

For a fuller explanation of CHAID please see Annex A, where the full outputs from the model can be viewed.

The CHAID analysis allows us to identify case characteristics where payment is particularly prevalent. As discussed earlier in this chapter 4% of claimants had not been paid in full. Focusing on these, CHAID analysis has been used to identify the factors that have the strongest relationship with non-payment.

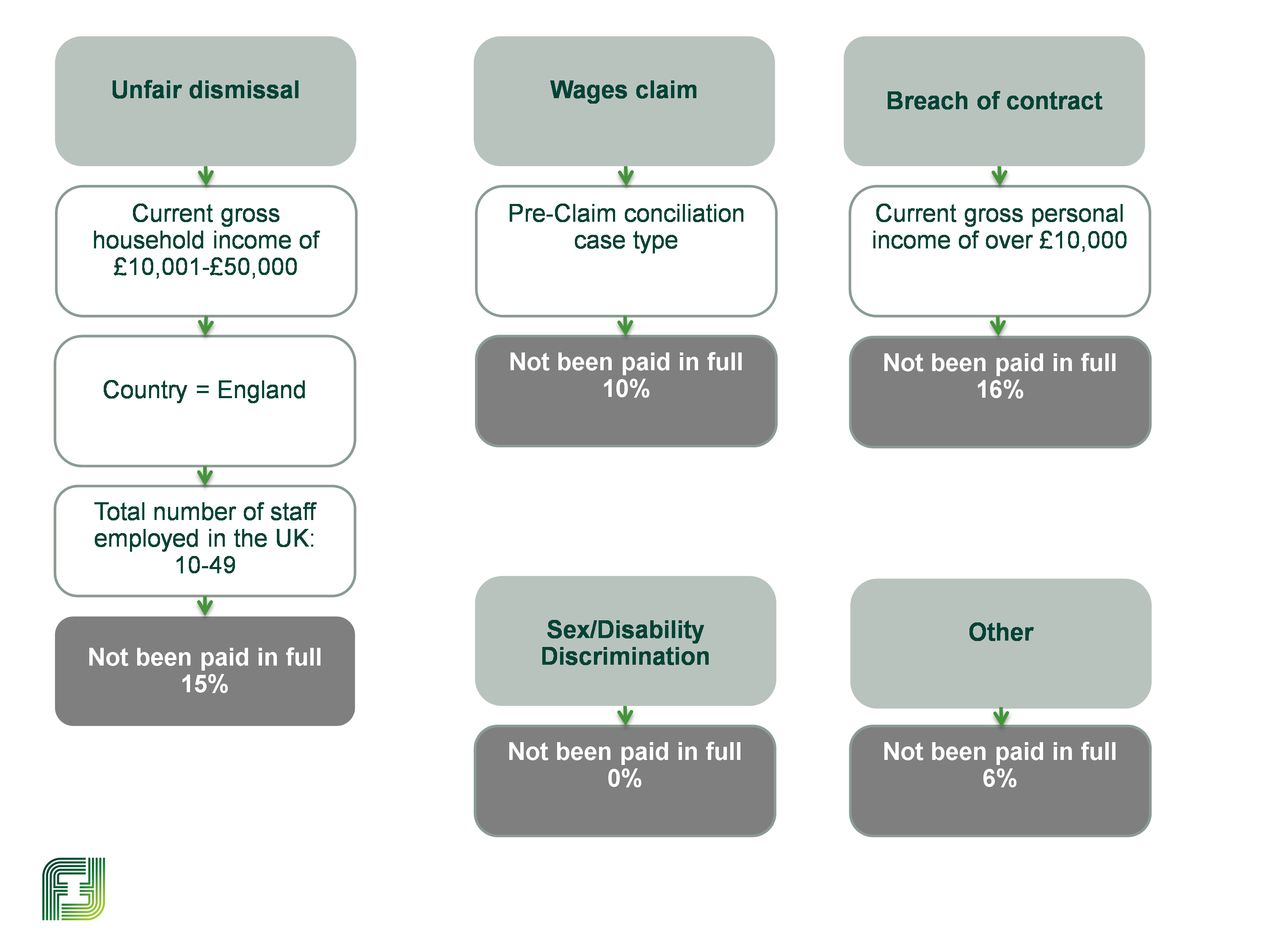

The analysis shows us that main jurisdiction is the strongest predictor of non-payment of settlement. The way the CHAID analysis works then is to split the sample by main jurisdiction, and identify the next strongest predictor for each group. This section will outline the pockets that have the lowest proportion of settlements paid in full within the main jurisdictions.

Figure 5.2 shows the pockets in which the levels of non-payment were highest amongst the main jurisdictions. Within the unfair dismissal cases the highest levels of non-payment were amongst those whose current gross household income was £10,001 to £50,000. The country of the claimant and the size of employer were further predictors.

For cases where wages claim was the main jurisdiction the main predictor was case type (i.e. highest levels of non-payment where the case was PCC) and when breach of contract was the main jurisdiction current gross personal income was the main predictor.

5.5 Reasons for part payment of amount agreed in settlement

2% of those who had monetary terms to their settlement had been paid in part at the time of interviewing (a total of 27 claimants. Due to the low base size we have not reported on percentages as the figures are not statistically robust. However the approximate proportions give a good indication of the experience of these claimants). The most common reasons given for the part payment were as follows:

a) being paid in instalments or paid off over time, which was given by around 2 in 5 (11 claimants)

b) a handful (4 claimants) mentioned that there had been a tax deduction

c) 2 claimants reported that there had been a disagreement over the sum owed between them and the employer

Of the 11 claimants who reported that the reason they had only been paid in part was because they were being paid in instalments or paid over time, 10 claimants stated that the payment instalments were ongoing (so there is no reason to expect that they would not receive their full settlement in time), although one claimant reported that payments had stopped.

All of the claimants who reported being paid part of their monetary settlement who knew when the payments had started said that this had been within 3 months of the settlement.

5.6 Reasons for non-payment of amount agreed in settlement

A total of 13 claimants (1%) had not received any payment of the amount agreed in their settlement. Of these, 8 claimants reported the reason they had not been paid the amount agreed was that the employer had refused to pay and 3 claimants said that the company they were claiming against no longer exists or has become insolvent.

5.7 Settlement of non-monetary terms

Two-fifths (38%) of claimants reported that their settlement had non-monetary terms. Of these, 72% reported that the non-monetary terms of their settlement had been met in full and a further 5% reported that they had been met in part. Only 1 in 9 (11%) claimants stated that the non-monetary terms had not been met at all.

Claimants who filed their claim against micro (1 to 9 employees) employers were more likely to report that the non-monetary terms of their settlement had not been met at all than those who filed their claim against large (250+ employees) employers (21% compared with 9%).

The most common reason for non-monetary terms having not been met in full (by 36% of claimants) was that they had not been needed yet (for example, if the settlement included the requirement for the employer to provide a reference but the claimant has not yet required this). This is a positive finding as there is no reason to expect that these terms will not be met in full, when they are required. However, 15% of claimants whose non-monetary terms had not been fully met said this was because the employer had refused to do so, and 7% reported it was due to delays caused by the employer. A further 5% said that the employer was unable to meet the terms of the settlement.

5.8 Enforcement of settlement

Claimants may seek to enforce a settlement if an employer does not pay the full value of the settlement via the courts. In England and Wales there are 2 main options available to claimants – they can file a case with the county court themselves, or for a fee of £60 they can, via the fast track scheme, use the services of a High Court enforcement officer to act on their behalf for this process. In both cases the enforcement claim goes through the county court. Only those based in England and Wales who did not have a conditional settlement were eligible (and therefore asked about) the fast track scheme in Scotland, claimants may engage a sheriff officer to enforce the settlement should they have a copy of the COT3.

The majority of claimants (93%) who had monetary terms included in their settlement received payment without needing to resort to enforcement.

Overall only 4% of claimants had pursued enforcement of their settlement. The low proportion of claimants using enforcement reflects the fact that the vast majority who had monetary terms to their settlement had been paid in full. Of those that pursued enforcement the majority (91% – 50 claimants) had subsequently been paid their settlement in full; of the remaining 7 claimants, 5 reported the enforcement action was still ongoing (suggesting the 'success rate' of enforcement action may be even higher if any of these cases end in payment).

None of the claimants based in Scotland had engaged a Sheriff Officer to enforce their settlement. 4% based in England and Wales had filed their case with the county court directly and less than 1% had pursued enforcement via the fast track scheme.

Claimants who used enforcement action tended to initiate this action soon after the settlement; a third of claimants who took enforcement action commenced this action within a month of the settlement being made; overall three-quarters (74% – 31 claimants) had begun enforcement action within 3 months of receiving their COT3.

5.9 Satisfaction with enforcement

Overall satisfaction with enforcing settlements through the County Courts was high. Of claimants who pursued enforcement and whose case was now closed, 67% (32 claimants) responded that they were either very or fairly satisfied with the outcome of enforcement; just 12% (6 claimants) were dissatisfied.

Over 7 in 10 (71% – 37 claimants) of those who had pursued enforcement through the County Court were very or fairly satisfied with how their case was handled; just 13% (7 claimants) reported that they were dissatisfied.

There were not enough claimants using fast track to report robust findings for this group (although of the 3 who had used it, all were satisfied with both the outcome and process of enforcement).

6 Conclusions

The research findings show that the COT3 settlement system is working well with a very high proportion of COT3s being settled in full.

Most (92%) settlements involved some form of monetary compensation and the vast majority (96%) of claimants who had monetary terms to their settlement had been paid in full by the time of the interview. Only 1% had not been paid at all.

The monetary settlements had been obtained largely in full (93%) without resort to enforcement. Without resorting to enforcement 2% had been paid in part and 1% had not been paid at all. Only 4% had resorted to enforcement and the overwhelming majority (91% – 50 claimants) of these had subsequently been paid in full. 2 claimants had been paid in part following enforcement and 3 claimants had not been paid at all.

Furthermore, these monetary settlements were also generally paid quickly with 95% of those who had been paid in full being paid the full amount within 3 months.

There are a number of features of the claim that might impact on likelihood of being paid in full which include:

- track type - claimants with fast track claims were less likely to have been paid than claimants with standard or open track claims

- case type - individual conciliation (IC) cases were more likely than pre-claim conciliation (PCC) cases to have been paid

- the size of employer against which the claim is made - with claims against larger employers more likely to result in payment

Those with non-monetary terms as part of their settlement (38% of claimants) also generally reported that these non-monetary terms had been either met in full (72%) or part (5%). However, a sizeable minority (11%) of these claimants reported that the non-monetary terms had not been met at all. The most common reason given for this was that they had not been needed yet (36%) but 15% said that this was because the employer had refused to do so.

Multivariate analysis indicates that the factor that is most likely to determine non-full payment of the settlement is main jurisdiction. The next strongest predictor for non-full payment of unfair dismissal cases was current gross household income of £10,001 to £50,000 and for wages claims those that were a PCC case rather than IC were less likely to receive full payment. Other important factors included income levels, size of employer and country.

Finally, while prior experience and confidence with legal issues among claimants was fairly low most claimants (60%) agreed that they understood the options available to them should their employer not fulfil the settlement terms. However, around a fifth (21%) disagreed which suggests that a sizeable minority have not taken on board the information contained in the letter accompanying the COT3.