Disclaimer

This analysis was prepared for Acas by Professor Richard Saundry of the University of Sheffield Management School and Professor Peter Urwin of the Centre for Employment Research, University of Westminster.

The views in this report are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect those of Acas or the Acas Council. Any errors or inaccuracies are the responsibility of the authors alone. This paper is not intended as guidance from Acas about how to manage disputes in the workplace.

Foreword

Acas has been preventing and resolving conflict at work for over 45 years. Thanks to our catalogue of independent research, we have crafted our experience and insights into a narrative about conflict that everyone can follow. This aims to explain what it is, why it matters and what can be done to both learn from it as well as manage it.

In the midst of a pandemic, and an economic recession, people are naturally reluctant to hear any advice that doesn’t help them to save money. Putting the pound sign in front of the cost of conflict at work undoubtedly grabs the headlines. That’s why this piece of research is a landmark event and hopefully one that will really ignite the debate about taking conflict more seriously.

The headline statistics are startling – in total, the cost of conflict to UK organisations was £28.5 billion – the equivalent of more than £1,000 for each employee. Close to 10 million people experienced conflict at work. Of these, over half suffer stress, anxiety or depression as a result; just under 900,000 took time off work; nearly half a million resigned, and more than 300,000 employees were dismissed. We are grateful to the CIPD for the survey data that provided the basis for many of our calculations.

We know that early intervention in conflict saves money, time and promotes better wellbeing: our new analysis provides employers with a new reality check. Of course, this analysis represents a snapshot and one taken before the dramatic upheaval to working lives caused by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. But I would argue that the crisis underlines the importance of waking up to conflict at work as an issue that should be considered from board level downwards.

Anecdotal reports and research to date suggest that conflict was suppressed during the height of the pandemic. This is also backed up by analysis of calls to our helpline relating to disputes. But as working life returns to some form of new normality in 2021, it is likely that insecurity, rapid change and continuing economic pressures will lead to a re-surfacing of conflict between individuals.

There are 3 strong messages to take from this report. Firstly, ‘conflict competence’ is an essential ingredient in good management and it has a positive impact on organisational effectiveness and performance. Secondly, there is a critical time to intervene. This is before conflict reaches formal workplace procedures, since at this point there is a greater likelihood of resignations, presenteeism and sickness absence. And, thirdly, while conflict can be very bad and damaging to people and a business, it can also be creative. Conflict that asks questions and challenges prevailing ways of doings things, does give us the opportunity to create fairer and more inclusive workplaces in the future.

Susan Clews, Acas Chief Executive

Executive summary

This report is the first to systematically map the incidence of conflict across UK workplaces, showing how this translates into impacts for individuals and their employers, and estimating the overall cost to UK organisations.

Key findings

- In 2018 to 2019, just over one-third (35%) of respondents to a CIPD study reported having experienced either (i) an isolated dispute or incident of conflict (26%); and/or (ii) an ongoing difficult relationship (24%) (including conflict with parties external to the organisation) over the last 12 months. Using these findings, we estimate that 9.7 million employees experienced conflict in 2018 to 2019.

- The vast majority of employees who experienced conflict stayed with the organisation and just 5% resigned as a result. A slightly higher proportion of respondents reported taking time off as sickness absence (9%). However, 40% reported being less motivated and more than half (56%) reported stress, anxiety and/or depression.

- We estimate that an average of 485,800 employees resign each year as a result of conflict. The cost of recruiting replacement employees amounts to £2.6 billion each year whilst the cost to employers of lost output as new employees get up to speed amounts to £12.2 billion, an overall estimate of £14.9 billion each year. A further 874,000 employees are estimated to take sickness absence each year as a result of conflict, at an estimated cost to their organisations of £2.2 billion.

- The vast majority of those who suffer from stress, anxiety and/or depression due to conflict continue to work. This ‘presenteeism’ has a negative impact on productivity with an annual cost estimated between £590 million and £2.3 billion.

- 1 in 5 employees take no action in response to the conflict in which they are involved, while around one-quarter discuss the issue with the other person involved in the conflict. Just over half of all employees discuss the matter with their manager, HR or union representative. In total informal discussions cost UK organisations an estimated £231 million each year.

- 5% of respondents took part in some form of workplace mediation, whether internally or externally provided, in 2018 to 2019 at an estimated cost of £140 million. Nearly three-quarters of those who underwent mediation (74%) also reported that their conflict had been fully or largely resolved. While this points to potential efficacy of the process in terms of resolution, the wider impacts were more mixed, as we discuss in more detail below.

- We estimate that there are an average of 374,760 formal grievances each year. The average cost in management time of a formal grievance is estimated at £951, giving a total cost across the economy of £356 million. In addition, there are an estimated 1.7 million formal disciplinary cases in UK organisations each year. The estimated average cost of each disciplinary case is approximately £1,141 – resulting in an economy-wide total cost of £2 billion. In addition, our estimates suggest that an average of 428,000 employees are dismissed each year and replacing them costs UK organisations an estimated £13.1 billion.

- We calculate that 136,249 early conciliation (EC) notices were submitted across the UK, including 132,711 submitted to Acas in 2018 to 2019, indicating an intention to pursue an employment tribunal claim. The total cost of management time spent dealing with potential and actual litigation is estimated at £282 million each year with a further £264 million spent on legal fees. In addition, we calculate that £225 million in compensation is awarded against employers per year.

- The largest proportion of the costs of conflict are connected to an ending of the employment relationship – either through resignation or dismissal. Costs in the early stages of conflict are relatively low – these start to mount if employees continue to work while ill and/or take time off work through sickness absence. The use of formal processes pushes costs higher, however costs escalate very quickly as soon as employees either resign or are dismissed.

- This analysis estimates the overall total annual cost of conflict to employers (including management and resolution) at £28.5 billion. This represents an average of just over £1,000 for every employee in the UK each year, and just under £3,000 annually for each individual involved in conflict (see endnote 1). It points to a clear link between the wellbeing of employees and organisational effectiveness.

Implications for policy and organisational practice

- Investment in effective and early resolution designed to build positive employment relationships may have a very significant return. The average costs of conflict where employees did not engage with their managers, HR or union representatives were higher than where such discussions took place. Furthermore, where conflict spiralled into formal procedures, costs were more than 3 times the costs associated with informal resolution.

- Organisations need to place much greater emphasis on repairing employment relationships in the event of conflict and taking action at early points to address issues of capability and poor performance. In addition, the analysis provides support for approaches to disciplinary issues that focus on learning and avoid blame. However, to achieve this, managers need to be provided with the core people skills to have quality interactions with their staff.

- The results provide strong arguments for a rebalancing of policy – decreasing the emphasis on legal compliance and effectiveness of the tribunal system, towards the resolution of conflict within organisations.

These findings are particularly salient given impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on employment relationships. They provide clear support for policies that seek to preserve employment where viable in the longer-term. It is likely that conflict will be more likely as organisations adapt to a new normal and problems suppressed during the crisis start to rise to the surface, requiring effective organisational responses. Finally, a more sustained shift to remote working and the potential acceleration of automation will create new challenges for the effective management of people, placing a premium on the skills needed to prevent, manage and resolve conflict.

1. Introduction

There is a growing body of research evidence that suggests the quality of management is a key part of solving the UK’s productivity puzzle (see endnote 2) . In particular, it is argued that organisations have tended to place too much emphasis on developing leaders concerned with strategy, while overlooking the importance of encouraging excellence in core management practices such as the management of poor performance, which are incorrectly seen as 'basic' and 'easy to replicate' (see endnote 3). If managers do not have these core competences, it is inevitable that they will come into conflict with individuals in their team. For example, previous Acas research has found that mismanagement of performance can often escalate into accusations of bullying (see endnote 4). More generally, the potential for conflict in relation to the conduct and capability of employees, means that conflict between managers and employees is central to management of the employment relationship (see endnote 5).

This report is the first to systematically map the incidence of conflict across UK workplaces, showing how this translates into impacts for individuals, and estimating the overall cost to UK organisations. Effective managers ensure that companies achieve performance goals, by managing the conflicts that can arise in pursuit of such outcomes and from the day-to-day interaction of people. From this perspective some of the costs we identify may be seen as unavoidable, as even the most skilled managers are not able to remove all instances of workplace conflict.

In some instances, managers may have little choice but to use disciplinary procedures when faced with serious misconduct, while investment in workplace mediation may prevent the damaging consequences of conflict. This study provides insight into the potential trade-offs between various forms of conflict resolution, by itemising the different elements of cost associated with individual workplace conflict and exploring how these are inter-related. For example, disciplinary action may be considered necessary to set standards of behaviour with the goal of improving efficiency, however this could trigger employee grievances and/or have negative impacts on employee well-being. By doing so, we provide important insights that enable employers and policymakers to identify where more effective responses are required, and the potential savings where managers are able to further develop conflict competence.

1.1 Analytical approach

This study estimates the cost to employers of conflict in their workplaces, rather than the overall net cost to the economy as a whole. For instance, whilst an employer will incur the costs of staff turnover associated with advertising for a new position, a standard cost benefit analysis (CBA) would not include such a cost. Payment by the employer to a recruitment/advertising agency represents a gain to another economic agent – a monetary loss to the company experiencing conflict, is a gain to the recruitment and advertising agencies, netting to zero. The same would apply for payments of employers and claimants to lawyers and other representatives (see endnote 6) . Our focus on the cost to employers is deliberate as the analysis seeks to primarily inform organisational responses to workplace conflict.

In arriving at our estimates, a purposively conservative approach is adopted throughout to better ensure that the costs to employers are not overstated. At each stage of our calculations we engage in a transparent discussion of estimates and the extent to which they can be attributed as an outcome of workplace conflict. Existing estimates of the cost of conflict lack this transparency and this limits their use as a basis for important discussion of organisational approaches. A good example is our discussion around estimates of dismissal, which form a useful basis for debate over the question of what proportion of dismissals are unavoidable?

In addition to this cautious approach to estimation, it is important to note that the estimate of cost to employers misses many wider costs borne by employees and society. For instance, our discussion of sickness absence and ‘presenteeism’ considers the wellbeing impacts associated with workplace conflict, but our focus is on the extent to which these directly impact employers and we do not capture the additional cost to individuals and their families. As with many other studies of the workplace we are limited to consideration of employees, as the evidence base for self-employed workers is too limited to attempt estimation.

Our approach to defining and estimating conflict aims to be transparent and pragmatic. We utilise self-reported measures from employees who perceive negative impacts on their performance and working lives from workplace conflict. Thus we take a data-driven approach to the definition of conflict and when considering these self-reported measures, we are focused on capturing costs that could be avoided by organisations. Our calculations become more challenging when considering the costs of resignation and dismissal, as this pragmatism extends to an acceptance that some amount of turnover is inevitable - a key challenge is identifying the costs of conflict that could be avoided with more effective management and workplace processes. At each stage of the following calculations we flag where this is an issue, Section 3.5 summarises the decisions made, and a technical appendix provides additional detail.

There is no one source of data that allows the creation of estimates. We draw on survey data from the CIPD collected in 2019 (see endnote 7); 2017 to 2018 data from the Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications (SETA, 2018) (see endnote 8); and for some of our parameters we draw on the Workplace Employment Relations Study (WERS), conducted in 2011 and published in 2014 (see endnote 9). We aim to provide an estimate of the ‘usual’ or average annual cost of conflict that is inherent in UK workplaces, which negatively impacts productivity each year. All the sources used pre-date the first lockdown in March 2020, so our figures are not skewed by events of the previous year. As the foreword implies, the £28.5 billion estimate we arrived at will likely be a lower bound for what can be expected in 2021 to 2022.

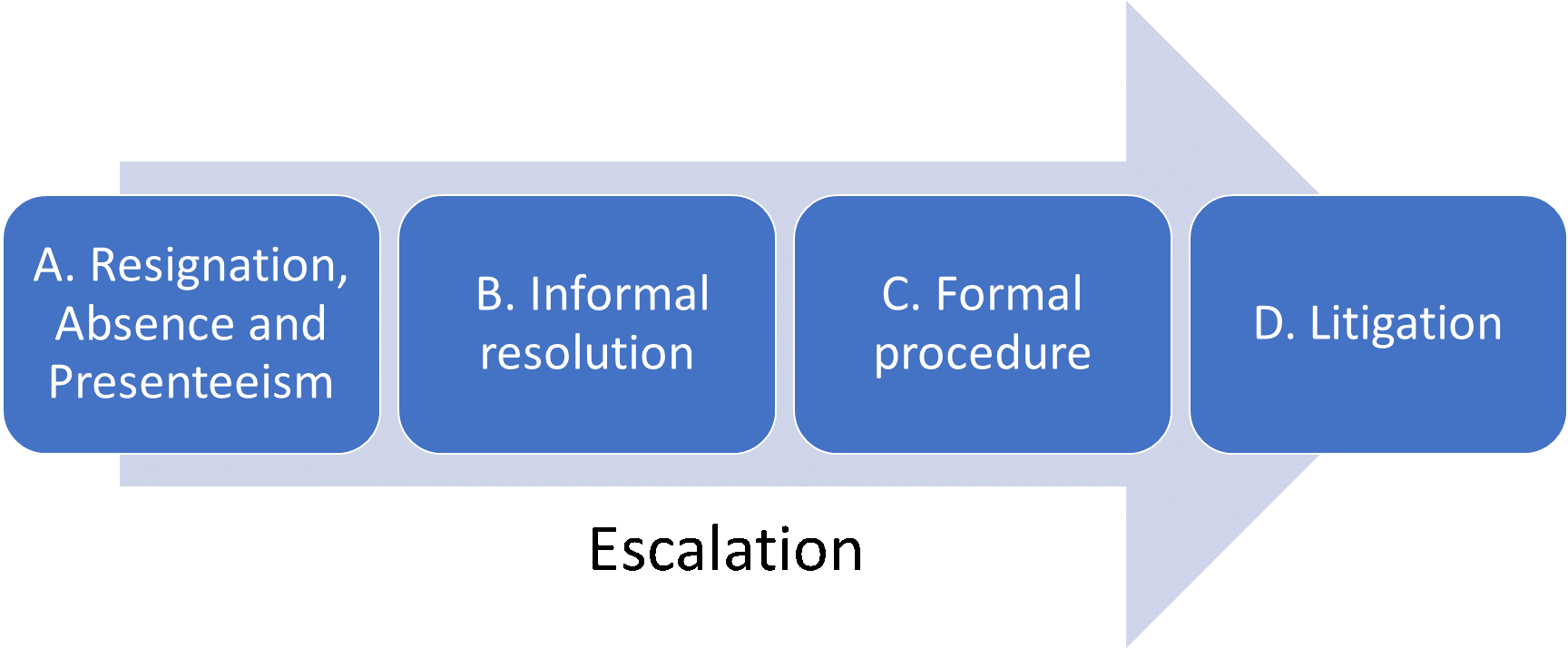

We measure conflict at 4 stages, broadly reflecting the levels of potential escalation:

- individuals who report isolated disputes or ongoing difficult relationships, and estimate the costs of resignation, absence and reduced productivity

- costs incurred by organisations in attempting to resolve issues through informal discussion – either between the individuals themselves or with line managers, HR practitioners and/or employee representatives

- the use and cost of more formalised mechanisms including workplace mediation, disciplinary and grievance procedures

- the extent of extra-organisational conflict, including that which manifests in Acas early conciliation (EC) notices, and in some cases, employment tribunal (ET) claims

Section 2 begins by defining conflict and setting out our conceptual approach to estimating the cost of workplace conflict. Section 3 then draws on a variety of quantitative evidence to examine the nature and extent of individual conflict, before providing estimates along our four dimensions. Section 3.1 presents estimates of the impact that conflict has on individuals and the implications for productivity; sections 3.2 and 3.3 consider the costs incurred from informal resolution, and the operation of formal procedure within workplaces, respectively; whilst section 3.4 considers the costs of litigation for conflict that is not resolved within the workplace.

Section 3.5 draws together these calculations and presents an overall estimate of the cost of conflict. Section 4 utilises these estimates to explore how costs vary across different stages of the conflict lifecycle and the conflict resolution process. This points to important implications for policy and practice relating to the effective management of conflict, which we discuss in the concluding section 5 of the report.

2. Framework for estimation

2.1 Conceptualising individual conflict

Not everybody turns up for work each day fully committed to the vision and mission of their organisation and its leaders. However, the suggestion that conflict is inevitable, given the contested nature of the employment relationship, runs counter to the unitarist perspectives that have increasingly dominated contemporary human resource management (HRM) (see endnote 10). Instead, conflict is typically portrayed as a ‘contagion’, created through poor communication or antagonistic ‘trouble-makers’. Moreover, workplace relationships are assumed to be harmonious by default, with all conflict avoidable through effective management.

In contrast, this analysis adopts a pluralist frame of reference, which accepts that conflict is an inherent component of organisational life. Individuals have differing opinions, values and goals and, as De Dreu argues, workplace conflict arises when these are ‘thwarted… by an interdependent counterpart’ (see endnote 11). Belanger and Edwards (see endnote 12) (2013:7) emphasise conflict from ‘underlying antagonisms or clashes of interests’, which can arise across employers and employees in the organisation, and in the management of work (see endnote 13). To be clear, we simply recognise that not all workplace actors are aligned in their opinions, values and goals and therefore some amount of underlying conflict is unavoidable. While this is represented in its purest form in conflict between manager and employee, it should also be acknowledged that peer to peer conflict can also develop from differences in attitudes and behaviours that do not directly flow from the employment relationship (see endnote 14).

The effective management of these underlying conflicts, through negotiation, discussion and sometimes the application of process and procedure, is central to organisational success. This can limit negative impacts but can also be argued to have the potential for positive outcomes in the longer term, through creative problem-solving and the deepening of relationships, which comes through effective dispute resolution (see endnote 15). Where this is not the case, economies and societies incur costs from conflicts that are inherently ‘avoidable’, and it is these costs that we estimate.

2.2 Measuring individual conflict

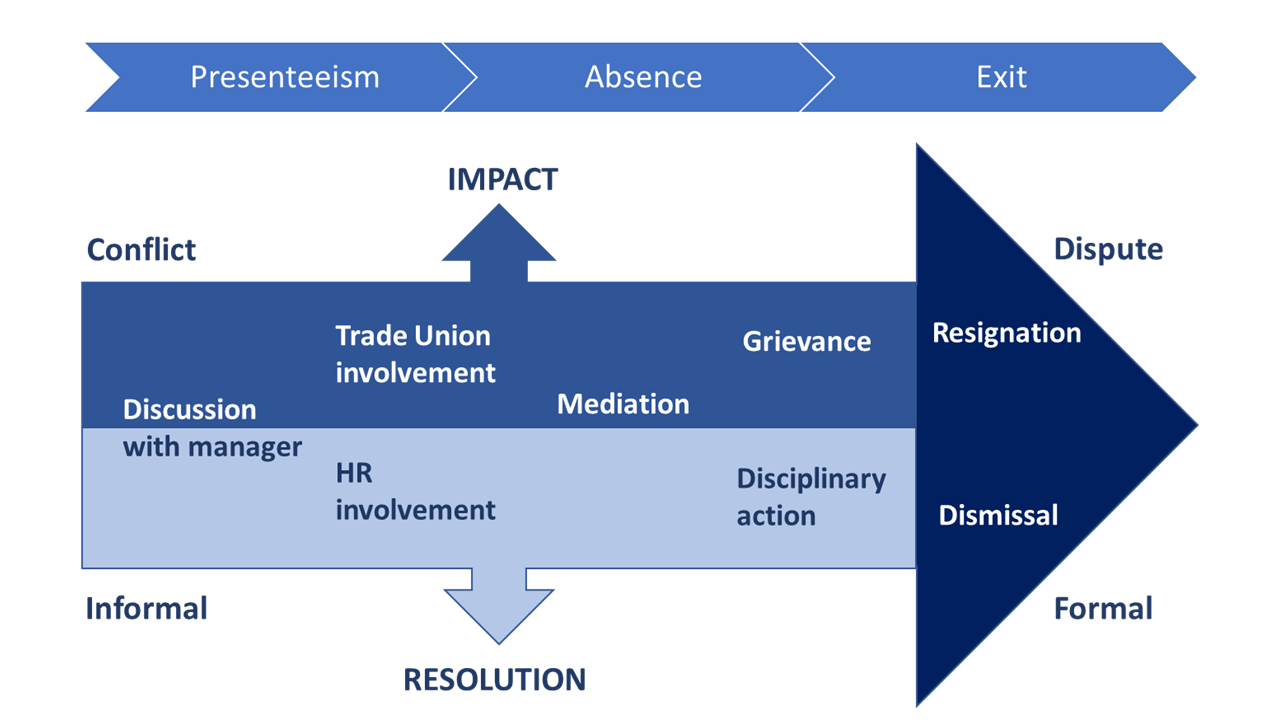

We estimate the costs of individual conflict across 4 dimensions (see Figure 1 below):

[A] The organisational costs incurred through impacts on the individuals involved in an isolated conflict or relationship breakdown between two employees, or a manager and a member of their team. These costs include the costs of resignation, absence and presenteeism, where individuals continue to work despite being unwell as a direct result of conflict at work.

[B] The costs of attempts to resolve issues through informal discussion – issues may be brought to the attention of a manager, HR practitioner and/or trade union representative. The time they spend dealing with the conflict will represent a cost to the organisation.

[C] The costs of formal process and procedure – if conflict cannot be resolved through informal discussion, formal processes or procedures can be activated. These include disciplinary action, grievance processes and workplace mediation, which all incur costs.

[D] The costs of litigation – if the issue is still not resolved, the employee may escalate the issue by submitting an early conciliation (EC) notice and potentially seek legal redress through an employment tribunal (ET) claim.

Estimating costs at each stage of Figure 1 presents challenges, as there are data limitations. The most authoritative source we draw on to populate the majority of estimates at [C] is the Workplace Employment Relations Study (WERS), most recently conducted in 2011 and published in 2014. Whilst this study is dated, it remains the most authoritative large-scale survey of employment relations in the UK; providing measures of the incidence of visible, formal manifestations of conflict in the workplace including grievances, disciplinary cases and dismissals. WERS also provides some detail on employment tribunal (ET) applications, but for the majority of estimates relating to this level of escalation [D] we draw on the 2018 Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications. Unfortunately, neither of these series provide information on [A and B], the less visible ‘relationship problems’ and low-level interpersonal conflicts where no action is taken, or informal approaches are adopted. Many of these issues do not escalate to the level of formalised workplace processes, but as we shall see they have the potential for large productivity impacts.

To estimate these impacts, we draw on online surveys conducted by YouGov for the CIPD in 2014 and 2019, using a sample of individuals from the YouGov GB panel, selected and weighted to be representative of the UK workforce. In 2019 the achieved sample for the employee survey was 2,211 adults, with fieldwork undertaken between 16 August and 3 September 2019; and in 2014 responses were secured from 2,195 employees. These studies are extremely valuable for our estimates of workplace conflict, but they do have limitations. To calculate our headline estimates we utilise figures from the 2019 survey, but also report an estimate arrived at using the 2014 survey when summarising our findings in Section 3.5. This helps to mitigate concerns over (i) sample size and (ii) the use of purposive non-probability sampling (see endnote 16).

The CIPD survey is particularly useful in 3 ways. First, it is the only available data that explores informal aspects of conflict management and resolution, enabling us to estimate costs at stages (A) and (B) of Figure 1. Second, it relies on reports from employees rather than management respondents, and we are therefore able to capture impacts of conflict that may remain ‘hidden’ – for example presenteeism. Third, it tracks individual experiences through the lifecycle of the conflict in which they are involved, which helps us to minimise the risk of double counting.

3. Conflict in the workplace

This section sets out our approach to estimation of the costs of workplace conflict in relation to the 4 stages of Figure 1, utilising the CIPD Workplace Conflict Survey (2019), WERS (2011) and SETA (2018). As suggested previously, we do face data limitations and where there are information gaps, we describe in detail our approach. This ensures we provide transparent estimates on which to base discussions across policy, government and business leaders.

3.1 Absence, resignation and presenteeism

We know from 2019 CIPD survey data that just over one-third (35%) of respondents reported having experienced either (i) an isolated dispute or incident of conflict (26%); and/or (ii) an ongoing difficult relationship (24%) (including conflict with parties external to the organisation) over the last 12 months. If one narrows this to only include conflict with another member of the organisation, the overall incidence falls to 29%.

For the purposes of this paper we use the definition of conflict which includes work-related conflicts with those outside the organisation (see endnote 17). On this basis, we estimate that 9.7 million employees experienced conflict in 2018 to 2019. Although some of these individuals may have been involved in the same conflict, they are potentially impacted in different ways with discrete implications for organisational cost.

More than three-quarters of those who reported conflict also reported a demonstrable impact. Importantly, this includes the 22% who did ‘nothing’ in response to being involved in conflict, but nonetheless experienced negative impacts in terms of wellbeing and workplace engagement. Figure 2 sets out the main reported impacts of conflict at [A] of Figure 1.

Source: CIPD Workplace Conflict Survey (2019)

Base: All respondents who report impacts from conflict (n=644)

Note: Respondents could select more than 1 impact so % sum to more than 100%

Figure 2 suggests that the vast majority of employees who experience conflict stay with the employer, with just 5% resigning as a result. A slightly higher proportion of respondents reported taking time off as sickness absence (9%). The most widely felt impacts were less tangible, with 1-in-5 being less productive, 40% less engaged and over half (56%) reporting stress, anxiety or depression. These % add to more than 100, as each employee can report that conflict led to stress, anxiety or depression that impacted their workplace productivity; this became worse and led to increased sickness absence; and eventually resignation. Such cases are relatively rare, but there are significant numbers who report, for instance, both reduced motivation; and stress, anxiety and depression. Each stage of the following discussions makes clear how we include relevant impacts and avoid double-counting.

3.1.1 Resignation

It is relatively straightforward to estimate the cost to the organisation of resignation (see endnote 18). Using the 2019 CIPD data, we estimate that 485,800 employees resign each year as a result of conflict. Work conducted by Oxford Economics (see endnote 19) suggests the cost of staff turnover can be measured across 2 dimensions.

First, average costs of recruitment (and some 'replacement costs' such as induction training) are estimated at £5,433 per employee; whilst lost productivity, as new recruits ‘get up to speed’, is estimated at £25,181 per employee. Consequently, we estimate the cost of recruiting replacement employees amounts to £2.64 billion each year, whilst the cost to employers of lost productivity as new employees get up to speed amounts to £12.23 billion, an overall total of £14.9 billion each year.

As suggested in Section 1.1, some amount of turnover is inevitable and even in the absence of workplace conflict, some resignations would be observed amongst these employees. In Section 3.5 we attribute a proportion of this cost and detail our reasoning in the technical appendix.

3.1.2 Sickness absence

Estimating the cost of absence due to conflict is less straightforward. According to the CIPD survey, 9% of those who experience conflict report taking sickness absence as a result. However, we do not have estimates of the average amount of additional time taken as absence by these 874,440 employees, as a direct result of this conflict. The approach we take to estimation when faced with this limitation (a common challenge in CBA) is to create estimates that provide us with orders of magnitude for the relevant impact.

One way of providing an estimate of the cost associated with this absence, would be to utilise the estimated median cost of sickness absence per employee [of £522 each year], reported in the 2016 CIPD Absence Management Survey (see endnote 20), and multiply this by the number of employees reporting absence as a result of conflict. Specifically, if 9% of all those reporting conflict respond by taking sickness absence, we can conclude that 3.2% of all UK employees took some time off sick as a result of conflict. This would suggest a total cost to the economy of approximately £456 million, but this implicitly assumes that all employees impacted by conflict take the median amount of absence underpinning this £522 estimate, and that all of this median amount is attributable to the conflict (see endnote 21).

Adopting a slightly different approach, we can draw on findings from the 2018 Labour Force Survey, that estimate 141.4 million working days lost due to sickness or injury, equivalent to 4.4 days for every UK worker (see endnote 22). However, we still face the same challenge if we attribute this average to the number of employees who report absence due to conflict – assuming that this is the amount of absence directly attributable to the reported conflict.

Considering other sources, it would seem reasonable to suggest that the average amount of absence taken by employees subject to conflict is higher. First, in the 2019 CIPD conflict survey, 91% of employees who took sickness absence due to conflict also reported suffering from stress, anxiety and/or depression. Second, according to LFS 2019 to 2020, amongst workers who report sickness absence due to work-related stress, anxiety and/or depression the average number of working days lost was 21.6 days (see endnote 23). This compares to an average of 17 days for those taking sick leave across all conditions.

From these various discussions we estimate that 874,440 employees (i) take an average of 21.6 days absence as a result of the reported workplace conflict; and (ii) assume that in the absence of this conflict, they would have taken 4.4 days, which is the average across all workers. Taking the difference (17.2 days) as the estimate of additional sickness absence attributable to the conflict, we estimate that 15 million days per year are lost through sickness absence as a result of conflict.

In order to estimate the cost of each day lost, we follow the methodology adopted by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (see endnote 24). This approach broadly follows that of Oxford Economics, assuming that in a competitive labour market, sickness absence reduces output by an amount that equals employee compensation; and the worker’s contribution to productivity.

Drawing on US research (see endnote 25), the Centre for Mental Health estimate this productivity impact as an additional 28% mark up on earnings. At the same time absence rates tend to be higher for employees on lower pay – therefore a 13.5% reduction is applied. A further reduction is then applied to take into account the fact that employees will bear some cost of absence through lower pay – for example most company sick pay schemes will reduce pay after a period or rely entirely on statutory provision (see endnote 26). Applying the most recent estimate from these calculations (see endnote 27) of £148 for the cost of a working day lost due to sickness absence, we produce an overall figure of £2.2 billion.

3.1.3 Presenteeism

In addition to the costs of staff turnover and/or sickness absence related to workplace conflict, Figure 2 suggests that large proportions of employees experiencing conflict report negative productivity impacts, reduced wellbeing [through stress, anxiety and depression] and/or reduced engagement [motivation/commitment]. How do we attribute a cost to these potentially overlapping impacts in a way that does not double count?

The international literature that attempts to assess the productivity impacts of reduced wellbeing and poor health, provides guidance in this respect; as it suggests that in addition to absence or resignation, working while ill (or ‘presenteeism’) is associated with reduced productivity (see endnote 28). There have been a number of attempts to assess the costs of presenteeism using a variety of tools including the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) and the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). However, this has given rise to a range of estimates.

McTernan et al found that presenteeism associated with mental health issues was a factor of 8 times greater than normal sickness absence (see endnote 29). As with other studies (see endnote 30), the authors calculate productivity loss by estimating a performance loss percentage, combined with median wage data. This suggests a productivity loss of between 23% and 28%, for mild to severe depression respectively. Woo et al's study of 106 employees in Korea found that those with a major depressive disorder rated their job performance during the previous 4 weeks as 22% below a control group (see endnote 31).

We need to be careful when translating estimates to the UK context (see endnote 32). Goetzel et al (see endnote 33) are useful in this respect, as they integrated 5 substantial independent studies and found that the productivity loss associated with presenteeism as a whole was 12%, and that associated with depression was 15.3% (see endnote 34). Parsonage and Saini (2017) conclude that a multiplier of 2x the cost of sickness absence provides a reasonable estimate of the cost of presenteeism (see endnote 35).

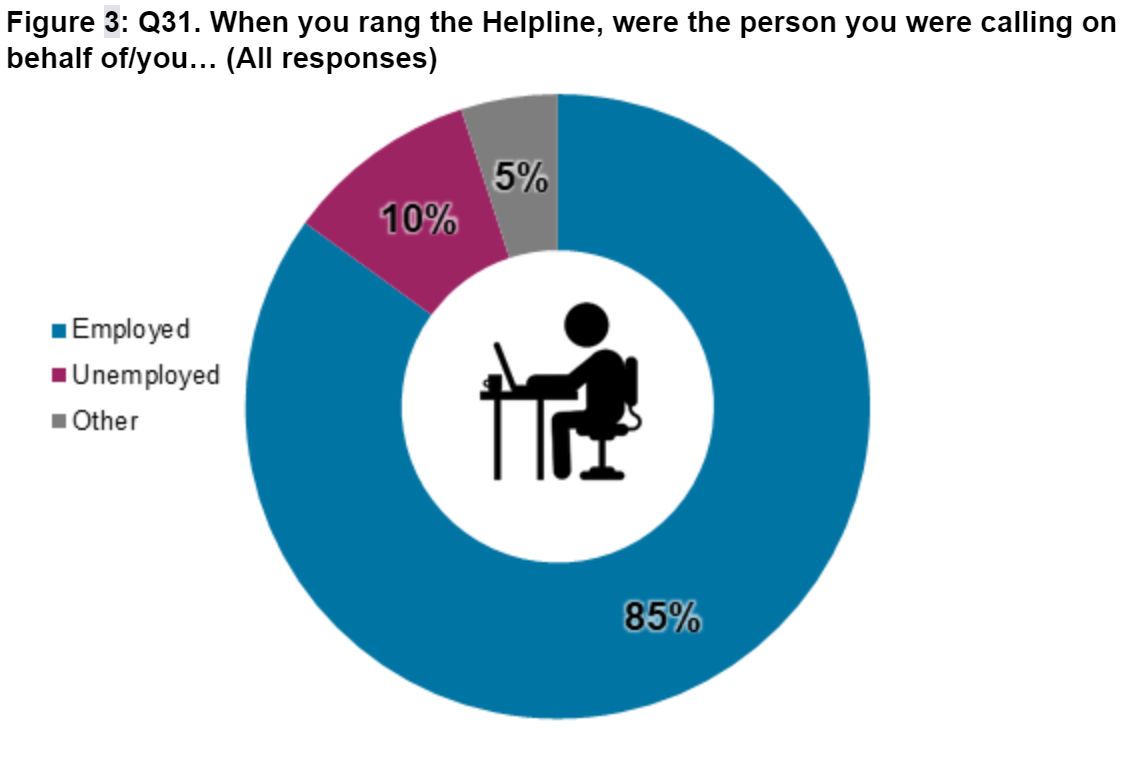

There are a number of challenges associated with estimation of the magnitude of impacts from presenteeism (see endnote 36), but it provides a useful framework for consideration of potentially overlapping productivity, engagement and wellbeing impacts. Of the 56% of employees involved in conflict who reported that they experienced stress, anxiety or depression as a consequence, 85% have the potential to exhibit ‘presenteeism’ as they did not take any time off work.

However, as Figure 3 (above) shows, 43% of this group reported neither reduced engagement nor negative productivity impacts, while 31% reported only reduced engagement. In the discussion below, we deliberately adopt a cautious approach and, in order to avoid double counting, we only include the 26% of employees who specifically reported reduced productivity. Nonetheless, it may be that CIPD survey respondents who report reduced engagement or negative wellbeing impacts from conflict, understate performance impacts. This is not an unreasonable suggestion, as these questions ask respondents to compare their performance in the counterfactual state of the world, where they are not subject to conflict, with their actual performance in a conflictual setting.

Thus, we may consider that impacts on wellbeing and engagement are ongoing – there is a continual feedback loop, and this conflictual context can become the new normal for the workplace. Employees begin to expect poor management capability and when asked, cannot perceive the impact on productivity, because they do not have experience of the counterfactual (working outside of the conflictual context, with better mental health and higher levels of engagement). However, speculation over issues of the counterfactual apply more generally and could be argued to drive estimates up or down. Does the academic evidence provide any guidance?

Studies exploring the link between wellbeing and productivity (see endnote 37) find that happy individuals are on average 12% more productive. This work also suggests that ‘bad life events’ such as bereavement or family illness lead to an estimated 10% decline in productivity. Other studies examine the link between subjective wellbeing and productivity in a representative sample of Finnish manufacturing businesses (see endnote 38). They find that a 1-point rise (on a 6-point subjective wellbeing scale) led to a maximum 9% increase in value added each hour, up to 2 years later (see endnote 39).

DiMaria et al (see endnote 40) explore the relationship between macro measures of total factor productivity and national measures of subjective wellbeing. Their findings suggest that while the scale of impact varies from country to country, wellbeing generates substantial productivity gains of 2 to 3% for each unit of wellbeing. The positive link between reports of subjective wellbeing and individual performance is also established in other studies (see endnote 41) and evidence suggests that positive effect makes individuals less likely to become involved in conflict (see endnote 42), re-enforcing our speculation on a possible circular relationship. Lyubomirsky et al also found that happy people are likely to be better problem-solvers and have superior conflict-resolution skills.

However, adopting a cautious approach to estimating the impacts of presenteeism, we include only the 26% in Figure 3 who report a fall in productivity. Based on the literature, we estimate that the average drop in productivity for each employee would be 12% and while the duration of this loss is likely to vary considerably, it would seem cautious to proxy the average duration by the same 17.2 days we estimate as the average number of sick days attributable to conflict, amongst workers who respond by taking a period of absence for stress, anxiety or depression.

This produces an equivalent productivity loss for each employee of 2.06 days, at an average cost of £237.14 each day (see endnote 43) and therefore a total estimated cost in lost productivity due to presenteeism of £589 million each year. At the other end of the scale, if one argued that all employees experiencing presenteeism see the same fall in productivity this would represent a total cost of £2.3 billion each year.

3.2 The cost of informal resolution

Good practice generally advocates the use of informal resolution, resolving workplace conflict through discussion (stage [B] of Figure 2). In recent years, there has been a notable emphasis in public policy to encourage and promote this type of early intervention, as it has the potential to defuse difficult issues, minimise negative impacts and preserve employment relations. These are positive actions taken to avoid escalation of conflict, but they do incur some cost to the organisation and here we provide estimates of these.

Again, it is worth noting our approach to avoidance of double counting. In the previous section we have focused on reported impacts from conflict, independent of whether individuals report that the issue driving conflict has or has not been resolved. To some extent this reflects data limitations, in that we do not have a clear timeline of conflict. For instance, we are not able to say if reported impacts occurred prior to a reported resolution; whether impacts from conflict continue to be reported, even after resolution is reported; or any combination of these. Thus, section 3.1.2 treats impacts from an individual reporting increased sickness absence [not resolved] in the same way as an individual reporting increased sickness absence [resolved].

Given that the analysis does not include any multipliers, we argue this is a cautious approach – if a conflict leads to sickness absence in the current period and is reported as unresolved, there is an argument for including similar impacts accruing in subsequent years. In contrast, one may consider that reported sickness absences associated with resolution may be less substantial than those who do not report resolution.

3.2.1 Informal discussion with the other party

The initial response of those involved in conflict would ideally be to discuss the matter informally with the other person or persons – reflecting the advice provided by Acas. The CIPD survey suggests that nearly one quarter (23%) of all respondents experiencing conflict reported doing this – an estimated 2.2 million discussions. We assume that each of these informal discussions takes an average of 30 minutes and that the cost of this time is equivalent to the median gross hourly pay for UK administrative occupations (Annual Survey for Hours and Earnings (ASHE) 2019).

This is a very conservative approach – we are only counting the time of one party to the discussion and using a relatively modest median wage for the cost of time. This is to reflect the potential for these informal discussions to be held outside of working hours, therefore having a lesser impact on output. Under these assumptions the estimated annual cost would be £16 million and even taking a less conservative approach the magnitude of costs still remains relatively small.

There is tentative evidence that this process has a positive impact in terms of resolution. 55% of those who had discussed the matter with the other party reported that the conflict was largely or fully resolved compared to 40% who had not entered into discussions. However, whether this had any cost benefits is less clear as there was no statistically significant association with any of the main impacts – resignation, absence, wellbeing, engagement or productivity.

Similarly, we are not able to account for the possibility that individuals selecting to attempt informal resolution, are tackling different types of conflict, when compared to those who adopt alternative responses. We are not attempting to identify causal relationships, so this is not a particular limitation of our study. However, it is worth noting that we are taking average impacts across a variety of different types of conflict and forms of resolution.

3.2.2 Informal discussion with line manager, HR and employee representatives

Over half (54%) of employees who attempted to discuss their conflict with the other person(s) also engaged with either their line manager, HR or an employee representative. This category is particularly important as it involves some type of organisational response and potential attempt at informal resolution. Once again this would generally be viewed as a positive attempt at early intervention.

The most common reported response was discussion of the issue with a line manager (40%); discussion with HR (11%); or with an employee representative (6%). Assuming that each one of these different discussions takes an average of 1 hour; that the cost of that 1 hour includes the employee’s time and manager’s time (estimated using median gross hourly pay from ASHE, 2019); we arrive at cost estimates of £155 million, £43 million and £17 million respectively. Of course, there is some overlap between these categories – for example almost half those who discussed the conflict with HR also discussed it with their line manager.

However, when combining categories, we estimate that just over half (51%) of respondents took part in at least 1 form of this in-house informal attempt at resolution. Using this 51% in place of our separate categories still provides a cost estimate just under £200 million, so it seems useful to retain the estimates of these 3 separate components of in-house informal resolution – the total cost of this time therefore amounts to £215 million.

Perhaps more notable than this cost of informal resolution, is the fact that 49% did not attempt any informal in-house resolution. Also, of respondents who discussed their problem with their manager, union representative or HR only 43% also stated that the problem had been fully or largely resolved. Moreover, there is little difference in the proportions who report their conflict as resolved, when comparing respondents who discussed issues with line managers, HR or trade union representatives.

In fact, impacts were generally more likely to be negative where such discussions had taken place. For example, 62% of those that engaged in informal discussions also reported that the conflict had a negative impact on wellbeing; compared to 50% who did not discuss the issue with HR, managers or trade union representatives.

There may be 2 possible reasons for this – first, managerial or union intervention is likely to be more necessary in relatively serious cases. Secondly, the involvement of managers, union representations or HR representatives may itself increase the stress and anxiety involved in the resolution process. However, it is worth noting that respondents were less likely to report resignation in cases where attempts at informal resolution had been reported. This possibly points to the role of such interventions in repairing employment relationships.

3.2.3 Workplace mediation

Workplace mediation is not (in a strict sense) an informal process – even if performed by internal staff mediators, it follows a specific structure, requires trained, qualified mediators and is a challenging experience for participants. However, it has been included here as it is (ideally) an early intervention and an alternative to formal grievance procedures. Furthermore, within policy debates, mediation is seen as part and parcel of a desired shift towards informal resolution (see endnote 44). Whether mediation is seen as an alternative or an addition to formal procedure is unclear from the CIPD data; as there is a suggestion that 43% of those taking part in mediation had also gone through a formal grievance or disciplinary procedure.

According to the CIPD survey, 5% of respondents took part in some form of workplace mediation, whether internally or externally provided (see endnote 45). This would imply that in 2018 to 2019 there was a total of just under half a million mediations. Considering the literature on workplace mediation (see endnote 46), this figure seems excessive and may be explained by respondents assuming that formal facilitated discussions with managers and HR represent ‘mediation’. Therefore, to estimate the cost of mediation we distinguish between external and internal; adopting a particularly conservative approach to the cost of internal mediation.

Acas conducted 270 mediations in 2018 to 2019 (see endnote 47). Our assumption that Acas conducts approximately one quarter of all external mediations leads us to estimate 980 ‘external’ mediations at an average cost of £1,500 (see endnote 48). This suggests that the bulk of mediations are conducted by internal mediators (whether trained or not) – and in these instances, we would suggest the cost is 1.5 days of a mediator’s time. This is a conservative estimate, as it does not include the cost of training internal mediators, operating an internal mediation service, or the costs of parties engaging with mediation. However, given we suspect that many respondents may be referring to facilitated management discussions when they think of ‘mediation’, this seems like a more reasonable assumption. On this basis the total cost of mediation is £140 million.

In terms of the impact of mediation, it is notable that nearly three-quarters of those who underwent mediation (74%) also reported that their conflict had been fully or largely resolved. While this points to potential efficacy of the process in terms of resolution, the wider impacts were more mixed, as we discuss in more detail below.

3.3 The cost of formal procedure

Where issues cannot be resolved informally, formal procedures may be initiated. For our purposes, we include in this category grievance and disciplinary processes. The CIPD survey suggests that 12% of respondents who report a conflict either initiate, or are subject to, grievance or disciplinary proceedings. Importantly this can be triggered by the employee bringing a grievance, by management through disciplinary action or a mutually agreed decision to engage in mediation.

The CIPD survey suggests that more than 2-thirds of cases subject to formal procedures had also been discussed with managers, HR practitioners or employee representatives. Nonetheless, that leaves just over 30% that bypassed informal resolution processes. Formal processes represent a significant cost to organisations, mainly in terms of managerial time but also in the costs associated with dismissal.

This is the point in our framework [Figure 1] where we move from consideration of stages [A] and [B] to those of [C] and, as a result, we now rely on evidence from WERS (2011), which measures the incidence of disciplinary sanctions and formal employee grievances. There are a number of advantages of the WERS data, not least that it avoids conflating disciplinary and grievance proceedings as a response to conflict. Disciplinary sanctions are a management action, while grievance processes are triggered by employees.

3.3.1 Employee grievances

First considering grievances, WERS 2011 found there were 1.35 formal grievances per 100 employees, which translates into an estimated 374,760 formal employee grievances. The CIPD estimate that each grievance takes an average of 5 days of management time. The cost burden of grievance (and disciplinary) procedures will undoubtedly vary a great deal depending on organisation size and sector, but using the CIPD average of 5 days and managers, directors and senior officials median hourly labour cost (derived from ASHE 2019), the average cost in management time of a formal grievance is approximately £950.50 and the total cost to employers is £356 million.

3.3.2 Disciplinary cases

In terms of disciplinary cases, WERS 2011 provides separate data on the incidence of sanctions and dismissals. We make the assumption that each sanction, and each dismissal, represents one individual disciplinary case. This does not include formal disciplinary cases that do not result in a sanction, so is likely something of an underestimate.

According to WERS 2011, the rate of disciplinary sanctions was 4.73 per 100 employees and the rate of dismissals was 1.54 per 100 employees. Assuming that each sanction or dismissal represents a disciplinary case, this translates into an estimate of just under 1.7 million disciplinary cases per year. The CIPD estimate that on average a disciplinary case takes up 6 days of management time – a figure that does not include the cost of facility time in unionised establishments or the cost of engagement by the parties to dispute.

Overall, the estimated average cost of each disciplinary case is approximately £1,141, resulting in an economy wide total cost of £2 billion. The average number of days taken for a disciplinary case seems high, but the rate of grievances and disciplinary sanctions is significantly higher in large public sector organisations, where processes are relatively complex and costly (see endnote 49) and this would serve to increase the average.

3.3.3 Disciplinary outcomes

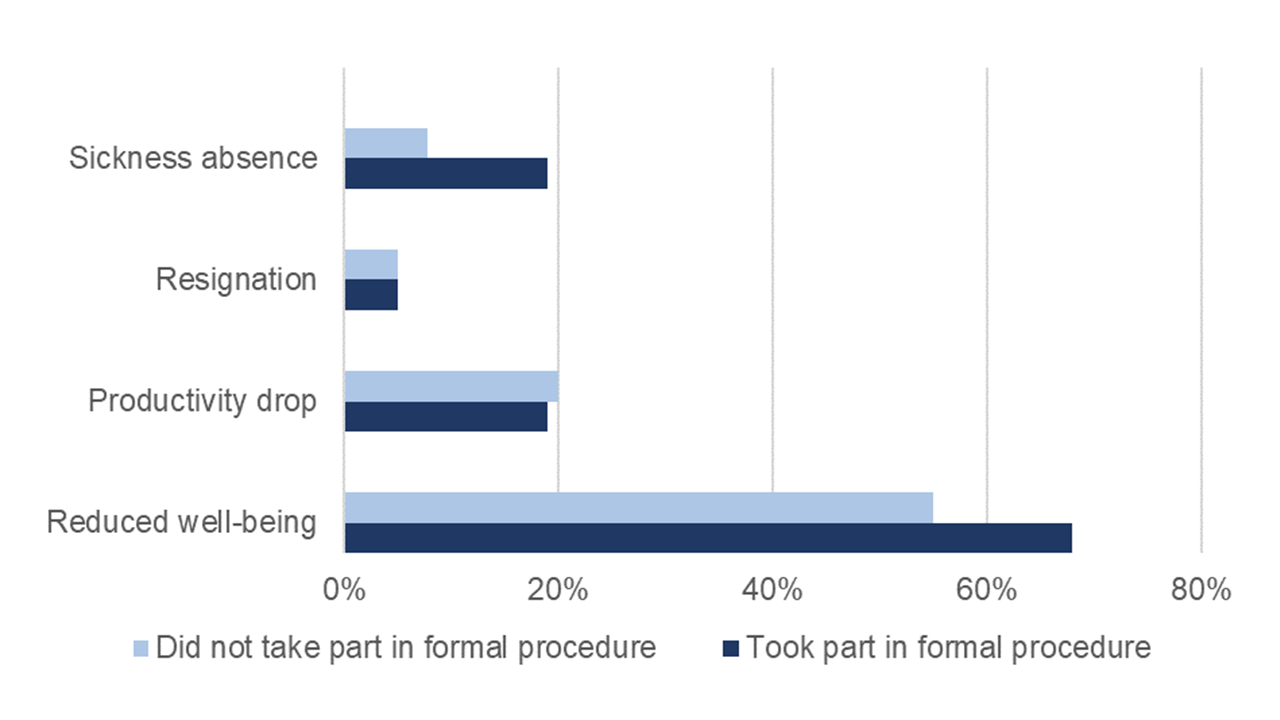

It is useful to consider differences in the reported impacts of conflict according to whether an employee engaged in formal or informal procedures, the majority of which are captured in Section 3.2. Figure 4 suggests that respondents who went through either grievance or disciplinary [formal] procedures also reported a range of negative wellbeing and productivity impacts, together with resignation and absence.

In particular, more than 2-thirds also report reduced wellbeing. Whilst we must again take care when comparing conflicts that may not be of the same nature, 19% of respondents took time off work, compared to just 8% of those who had not been subject to formal procedure.

Source: CIPD (2019)

Base: All respondents who report impacts from conflict (n=644)

Note: Respondents could select more than one impact so percentages sum to more than 100%

Assuming that a disciplinary dismissal (as opposed to a redundancy dismissal) will create a vacancy, we can take a similar approach to the estimation of costs, as in section 3.1.1 when considering resignation. Using the same figures from Oxford Economics (2014), the estimate of costs incurred filling this vacancy will be £5,433 for recruitment and £25,181 in lost earnings and output, as new recruits get up to speed. However, there is greater uncertainty over the estimated number of dismissals than when considering resignation.

The CIPD survey does provide us with an estimate of employees who report dismissal as a result of workplace conflict. This figure of 1% is the same in both the CIPD (2019) and CIPD (2014) surveys. Unfortunately, such a small % means we are certainly relying on responses from less than 20 employees and more likely less than 15, across both surveys combined. There is also concern over potential bias in responses around such a sensitive topic. To be clear, our use of the CIPD (2019) study to estimate the proportion of resignations is on the boundary of acceptability, with the 5% figure reflecting a number just above our cell size cut-off of 30 respondents. The 4% figure relating to resignations in CIPD (2014) is just under this cut-off, but across both studies we have some confidence in estimates.

To give an idea of how much a small variation impacts estimates, if we were to use a 1% figure, the estimated number of dismissals due to workplace conflict would be 97,160 – variation of 1 or 2 %-points either way makes a large difference. As with other areas of this study, we use alternative data sources to provide insight into orders of magnitude. The estimate from WERS 2011 that dismissals average 1.54 for every 100 employees implies an upper bound of 427,504 dismissals. Whilst we may consider this figure to be more reliable, there is now a question of where we locate between these 2 extremes?

In section 3.5 we discuss this issue further, detailing the point at which we locate between these 2 magnitudes (the technical appendix provides additional contextual information). Our challenge is that disciplinary action and even dismissal may be taken as evidence of both effective and ineffective management. An individual’s performance or conduct may not be acceptable simply because they are a poor match to a job – even in an ideal world, some amount of mismatch is ‘unavoidable’, as productivity is observed with error on appointment of a new hire . Dealing with a number of poor job matches may be considered a standard task of management.

How different managers handle difficult issues and how they manage their staff in general will determine what is avoidable and unavoidable. An effective manager may be able to resolve an issue at an early point, for example by helping individuals to improve skills; and if this is unsuccessful, there may be recourse to capability processes and ultimately dismissal. In contrast, if a poor manager does not tackle the issue, it spills over into ‘avoidable’ conflict amongst other staff and prolongs the negative impact on organisational productivity of the continued poor performance – adding significantly to the original challenge of ‘mismatch’.

Section 4 digs further into these issues, by considering a number of conflict escalation and early intervention scenarios. To aid transparency when considering the overall cost of workplace conflict, the discussion in section 3.5 sets out a rationale for our choice of estimate for the cost of recruiting replacement employees, which lies between £13 billion (using the WERS 2011 figure) and £3 billion (1% of all those reporting conflict).

3.4 The cost of litigation

If conflict is not resolved in the workplace either through informal discussion or formal procedure, employees can decide to make a complaint against their employer through the employment tribunal (ET). This is rare, and according to the CIPD survey only 1.4% of conflicts involve an employment tribunal claim being filed. From the employers’ perspective, WERS data found that in 2011, just 4 out of every 100 employers are subject to an employment tribunal claim (see endnote 51). Nonetheless, perceptions of the risk of litigation have been a major factor in shaping dispute resolution policy.

In order to bring an employment tribunal claim, all claimants must first notify Acas who will attempt to conciliate a settlement between the parties – what is known as ‘early conciliation’ (EC). The approach we take here is consistent with that taken in the estimation of conciliation in individual employment disputes (as described in Urwin and Gould, 2016; Urwin, 2020). This focuses on costs incurred by employers, employees and others involved in cases as they progress to various stages of the ET process, including hearings.

In the 2018 to 2019 operational year there were 132,711 EC notices received by Acas and with the addition of 3,538 cases for Northern Ireland, these form the basis for estimation of impacts for the UK (see endnote 52). Using this figure of 136,249 as the basis for our volume of EC notifications, we can use the 2018 to 2019 Acas Annual report and other sources to calculate that (1) 13% were COT3 settled (see endnote 53) and (2) 63% did not progress further, for reasons other than COT3.

This gives an estimate of 32,700 cases that did progress to ET and of these (3) 17.9% were withdrawn [5,853]; (4) 51.1% of cases reached a Settlement [16,710] and (5) 22.4% went all the way to a hearing [7,325]. This is our starting point - we then take each category (1) to (5) and attribute the costs associated with these different levels of escalation.

3.4.1 Management time

Management time costs are calculated by obtaining an estimate of the time spent by managers and other staff on a case that gets to one of these 5 stages of escalation (see endnote 54); then using ASHE 2019 to calculate the cost of this time for each case; and finally multiplying by the number of cases. Management and other staff time costs are only included for (i) EC cases between the submission of EC notice to the end of Acas conciliation and (ii) in SETA 2018, estimates of management time are similarly only those incurred during the ET process. More specifically, we estimate the following costs of managers and other staff time taken up by cases:

- cost of management time on all EC cases that do not progress to ET1 (categories 1 and 2) is estimated at £118 million, between submission of EC notice and the end of conciliation

- cost of management time on all cases that go through EC, progress to ET1 and are then withdrawn (3) is estimated at £34 million, between submission of EC notice and the end of the ET process

- cost of management time on all cases that go through EC, progress to ET1 and are then settled (4) is estimated at £85 million, between submission of EC notice and the ET settlement

- cost of management time on all cases that go through EC, progresses to ET1 and are then heard (5) is estimated at £45 million, between submission of EC notice and the ET hearing

Overall, the total estimated cost of management time in relation to litigation is £282 million.

3.4.2 Legal and other costs of representation

There are a variety of estimates of the legal costs associated with employment tribunal applications. The most robust of these is drawn from SETA 2018, which shows that 70% of respondents had day-to-day representation and 81% of these respondents paid wholly or partly for this assistance. The mean cost of representation was £55,551, which is clearly distorted by a small number of cases, with extremely substantial legal expenses. Therefore, for the purposes of this report we use the median cost of £5,000 to estimate the legal costs incurred by employers.

We cannot assume that SETA figures relating to representation at ETs apply across all those cases for which an EC notification is received, as representation is less prevalent at the EC stage (33% – see endnote 55). Therefore, we use a figure of 33% for the 76% of EC notifications that do not progress to the ET stage and 70% (multiplied by 81%) for the remaining 24% that do progress. In total the estimated cost of this legal representation to UK organisations is £264 million each year.

Overall, we believe this is a conservative estimate as it does not include those employers who receive ‘free’ legal representation through insurance or membership of employers’ associations. Moreover, between 6% and 18% of employers use HR practitioners and 5% to 10% use in-house legal services to provide representation at various stages of the employment tribunal process [though one may speculate that some of this may already be captured in our cost estimates of section 3.4.1].

3.4.3 Compensation payments

Compensation payments made by employers to employees are ‘transfers’ of resource between economic agents and would be excluded in standard CBA estimates of impact to the whole economy (see endnote 56); but are included here, as they are a cost to those employers subject to conflict. Compensation includes sums agreed as part of the 17,712 early conciliation notifications that are settled through a COT3 agreement and the 16,710 ET1 claims that are settled through Acas conciliation at the subsequent stage (a total of 34,422 settlements).

The median settlement in 2018 was £5,000. This produces a total for settlements of approximately £172 million. In addition, 9% of 94,332 claims disposed in 2018 to 2019 were successful at hearing, a total of 8,490. As no median award for all jurisdictions is provided in the available data, we use the median award for unfair dismissal cases in 2018 to 2019 which was £6,243. This produces an estimate of approximately £53 million and therefore the total cost of settlements and compensation to employers is estimated at £225 million.

Adding together the various components above, the annual cost of employment litigation to employers amounts to approximately £800 million.

3.5 Overall costs of conflict

Table 1 provides a summary of all cost estimates calculated in this section of the report. The overall total yearly cost of conflict to employers (including management and resolution) is estimated as £28.5 billion. This represents an average of £1,028 for every employee in the UK each year, and just under £3,000 (£2,939) annually for each individual involved in conflict.

As suggested in section 1.1, some amount of turnover, sickness absence and resignation or dismissal is inevitable, even in the absence of workplace conflict, so Table 1 only attributes a proportion of some of the costs we have detailed between sections 3.1 to 3.4.3.

Putting aside resignations and disciplinary dismissals for the moment and taking the remaining components in order they appear, we have an estimated cost of £2.2 billion for sickness absence – a figure that allows some amount of sickness absence, even in a world where avoidable workplace conflict is removed (Section 3.1.2). As suggested in Section 3.1.3, a cautious approach to estimation has been taken for impacts of presenteeism, only counting the 26% who report falls in productivity. The resulting figure of £590 million ignores many other employees who report negative wellbeing and motivational impacts, and depending on how one deals with employees who do not explicitly mention productivity impacts, estimated presenteeism costs could rise to £2.3 billion.

Under the subheading ‘the cost of informal resolution’, we omit the £16 million of estimated costs associated with informal discussion between the persons involved in conflict; and only half the £215 million cost of informal discussions with HR, line manager or unions is included. This approach is not ideal, as we have no specific parameters to justify the extent of this discounting, but it serves to highlight the fact that what we wish to capture here is the cost of conflict that is avoidable and some amount of resolution cost seems unavoidable, even in an ideal world.

This transparency is hopefully useful in forming a basis for wider debate, but ultimately the magnitude of these impacts is relatively modest. Even if we were to adopt alternative approaches for the estimation of employee grievances, disciplinary cases and components in the cost of litigation, these would remain modest relative to the costs of resignations and disciplinary dismissals – our approach of essentially only including one conversation is conservative.

To account for the fact that even in the absence of workplace conflict, labour markets operate with some amount of market failure (mainly driven by information failures) and are dynamic in nature, we discount the estimates presented in Sections 3.1.1 and 3.4.3 by 20%. This is driven by ASHE data that indicate an average of 20% of all employees can be considered as ‘job changers’ in more recent years (see endnote 57).

The technical appendix provides more background discussion on the pros and cons of this approach; Section 4 considers scenarios describing the various responses to workplace conflicts that have the potential for resignation or dismissal; and from this, readers can clearly see our justification for estimated cost of £11.9 billion for resignation and £10.5 billion for disciplinary dismissals in Table 1.

Table 1: Annual costs of workplace conflict

| Estimated costs of workplace conflict | Annual cost |

|---|---|

| Cost of resignation, absence and presenteeism | |

| Resignations | £11.9 billion |

| Sickness absence | £2.2 billion |

| Presenteeism | £0.59 billion |

| Total | £14.7 billion |

| Cost of informal resolution | |

| Informal discussion with HR, line manager and/or unions | £0.12 billion |

| Workplace mediation | £0.14 billion |

| Total | £0.25 billion |

| Cost of formal procedure | |

| Employee grievances | £0.36 billion |

| Disciplinary cases | £2.0 billion |

| Disciplinary dismissals | £10.5 billion |

| Total | £12.8 billion |

| Cost of Litigation | |

| Management time | £0.28 billion |

| Legal representation | £0.26 billion |

| Compensation | £0.23 billion |

| Total | £0.77 billion |

| Total cost of conflict | £28.5 billion |

£28.5 billion is our estimate of the cost of conflict that employers could reasonably avoid with more effective management and workplace processes. To give some idea of the sensitivity of this estimate to alternative approaches, we have made clear the range of potential values where there is particular debate. To add to this transparency, we have also calculated the estimated overall cost using only the figures from CIPD (2014) and a lower bound estimate for the costs of litigation (see endnote 58). This produces an estimate of £26.8 billion, 6% lower than our headline figure, and we suggest this provides some indication of the potential for variation around our estimate of £28.5 billion.

Conflict, and its effective management, is a critical issue for debate in organisations. The estimates presented in this report have strengths and limitations. The transparency of discussion around our estimates provides a useful platform for key aspects of this critical debate. For instance, the question of when dismissals are possibly warranted is one that needs to consider a variety of offsetting costs and in the following section these are considered using various scenarios.

4. Conflict escalation and early intervention

4.1 The escalation of conflict

The analysis to date has estimated different elements of cost, however, it is possible to locate these different elements (and different types of conflict) within a process of escalation. A simplified model of escalation and impact is provided in Figure 5 (below).

In basic terms, most workplace problems start as a clash of interests or a disagreement. At this point, they can often be resolved informally through discussion with the manager. If this is not possible or they are more serious, it may be necessary to involve other parties such as HR or representatives. This inevitably formalises the issue and it becomes more likely that there will be negative impacts in the form of presenteeism or possibly absence.

If the conflict is not resolved, semi-formal mechanisms such as mediation may be considered. The next stage of escalation would see the conflict become manifest as a dispute, with formal mechanisms such as disciplinary or grievance procedures enacted. This also implies more serious impacts and ultimately the potential for exit through resignation or dismissal. Outside the workplace, the final stage in this process would be litigation through the employment tribunal system. While this model is inevitably stylised, it does allow us to see how costs may begin to mount as conflict escalates.

4.2 The escalating costs of conflict

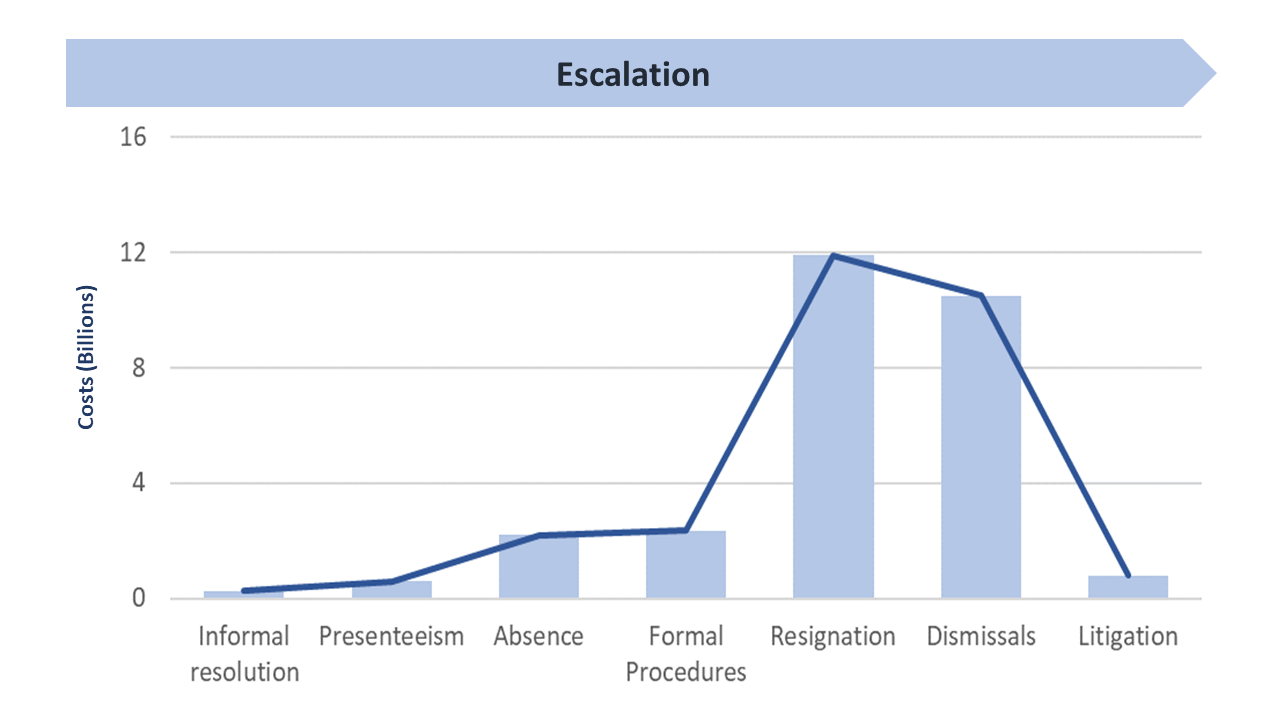

This is clearly illustrated if we use this model to organise individual components of the cost of conflict summarised in Table 1. Figure 6 suggests that costs in the early stages of conflict are relatively low – these start to mount if employees continue to work while ill and take time off work; and the use of formal processes can push costs higher. However, costs escalate very quickly as soon as employees either resign or are dismissed – this ‘hump’ is where the bulk of costs are contained.

Note: the graph in Figure 6 is based on the data in Table 1.

It is important to note that the development of conflict is not linear and we cannot precisely allocate costs along the timeline in Figure 6 – for example, absence and presenteeism can occur at any point and employees can resign before there is any opportunity to resolve conflict. In addition, we have been transparent in our discussion of how costs are estimated, as it is possible that some amount of the difference between [for instance] presenteeism and resignation in Figure 6, reflects the extent to which costs at these 2 stages are more or less easily observed.

Resignation is a distinct point in the employment relationship when the employer incurs clear costs – any estimates of the impacts stemming from presenteeism are harder to observe and have the potential to be compounded over many years. However, this representation is broadly reflective of workplace practice and is valuable in highlighting the cost implications of allowing the employment relationship to deteriorate and ultimately collapse.

4.3 Formality, informality and the cost of conflict

We can also try to develop a more precise idea of the costs at different stages of conflict management and resolution by using 2 slightly different approaches. First, we separate the respondents to the 2019 CIPD survey into 3 categories: those that did not take part in organisational processes of resolution (either informal or formal); those who engaged in informal processes of resolution, but took no further action; and finally those who were involved in formal disciplinary or grievance procedures.

The results of this analysis are telling – the first category involves almost half of those who experience conflict (approximately 4.6 million people every year), which suggests that organisational responses are failing to reach a significant number of those with workplace problems. While a proportion of these report not being affected by the conflict, 44% experience presenteeism, 5% take time off work and 7% resign – at an average cost per person of £2,324. The average cost of conflict for the second group, whose only response to the conflict is to discuss it with managers, HR practitioners and/or representatives, is £1,941, which is 16% lower even when taking into account the management time involved in informal resolution. Presenteeism and absence are higher in this group, perhaps suggesting that these cases may involve more complex issues. However, the lower cost overall is explained by a lower level of resignations (4%), which ‘tentatively’ (not least because of small numbers) points towards a link between informal discussion and repair of the employment relationship.

The third category comprises all those cases that are dealt with through formal procedure. Among these cases absence (21%) and termination of employment (12%) are much higher and while this includes the additional costs of the procedures themselves and legal action (in 7% of cases), it is the end of the employment relationship that primarily explains an average cost per employee of £6,405 – more than 3 times the cost of conflict handled solely through informal discussion.

Table 2 – Formality, informality and the cost of conflict

| HR issue | Neither informal or resolution nor formal procedure | Informal resolution | Disciplinary/grievance procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenteeism | 44% | 50% | 49% |

| Absence | 5% | 12% | 21% |

| Resignation | 7% | 4% | 7% |

| Discussion – manager | – | 79% | 40% |

| Discussion – HR | – | 27% | 35% |

| Discussion – union | – | 13% | 26% |

| Mediation | – | – | 15% |

| Disciplinary/grievance procedure | – | – | 100% |

| Dismissal | – | – | 5% |

| Legal dispute | – | 2% | 7% |

| Average cost per person | £2,324 | £1,941 | £6,405 |

4.4 Conflict management resolution and cost

An alternative approach is to examine a number of typical conflict resolution illustrative scenarios. In the analysis below we look at three different scenarios; in each case we set out different stages of the resolution process and cumulative costs to the organisation.

Scenario 1 is fairly typical of the dynamics of conflict, particularly in an organisation with insufficient channels of voice and where individuals don’t feel comfortable raising difficult issues. Here an individual feels that they have been treated unfairly at work by one of their colleagues. However, they do not feel able to make an informal or formal complaint. As a consequence of this conflict, the individual suffers from anxiety and depression, but continues to work (presenteeism). On the basis of the analysis above, this would incur an average cost of £489.46. If they then left the organisation as the situation remains unresolved, there would be a further average cost of £30,614 in costs of replacement and lost productivity. Overall, this scenario would result in an average cost of £31,103.

A realistic counterfactual is set out in Scenario 2 in which there is a more effective organisational response. In this case, the individual feels able to raise the issue with their line manager. Alternatively, a line manager could identify that the employee has a problem and encourage them to try to resolve it through discussion. Given the seriousness of the situation, we assume that the line manager would seek advice from HR and a union representative could also be involved.

A conservative estimate of the time needed to explore a complex situation would be 2 hours each of line manager time (£25.62 per hour), HR practitioner time (£25.62), union representative time (£14.34) and the 2 employees involved (£14.34) – a total of £188.52. A reasonable outcome of this initial intervention would be a referral to workplace mediation. Here we assume that an external mediator is contracted at a cost of £1,500 with an additional cost of 8 hours of the time of the 2 employees involved (£229.44). The total cost of mediation would be £1,729.44 and the overall cost of the resolution process would be £1,918.

It is important to note that this assumes no impact of either absence or presenteeism, which in turn implies that the issue has been managed quickly and efficiently. Of course, the longer this resolution process takes the more likely it is that the employees involved will suffer negative impacts with consequential costs for the organisation. Furthermore, this scenario reflects good practice by engaging mediation at an early stage, when success is more likely. If mediation is employed as a last resort, not only will costs have already escalated but it is much less likely to be effective (see endnote 59).

Figure 9 sets out scenario 3 where the issue is poorly handled by the manager. As research evidence has suggested (see endnote 60) this is not uncommon in UK workplaces, where levels of skill and confidence are such that managers often struggle to deal with complex and challenging personnel issues. The initial costs are relatively low, assuming a similar level of managerial and union intervention as scenario 2.

However, the failure to resolve this has negative implications. The employee refuses workplace mediation and instead decides to make a formal complaint through the grievance procedure. The employee then takes time off due to stress, anxiety and depression – a common feature of a) disputes involving bullying and harassment and b) those that escalate into formal procedure.

In the analysis above we estimated the cost of absence as a result of conflict on the basis that each employee absent due to conflict at work would take an average of 17.2 days. It is reasonable to assume that, given the aggravating nature of this conflict and the triggering of a formal grievance procedure, this would be significantly longer here – we therefore multiply this by 3 to provide a total absence of 51.6 days at a cost of £148 per day – a total of £7,636.80. The grievance procedure itself adds a further £950 to the overall cost. However, in this scenario, the formal procedure results in a resolution, so the overall cost to the organisation is £8,775.

While this is significantly more than the cost of successful and early informal resolution, it is less than the cost of scenario 1. This suggests that there are cost advantages to providing channels of employee voice (even when these are not well managed) as it has the potential to avoid exit and the significant costs attached to this. Nonetheless this is predicated on the fact that formal procedure will generate a sustainable resolution. If this is not the case, then costs will escalate as envisaged in scenario 4 (Figure 10). This follows the same path as scenario 3, but the grievance procedure results in the individual resigning and making an employment tribunal claim for unfair constructive dismissal.

As in scenario 1, it is when the employee resigns that costs begin to escalate rapidly. This adds an additional £30,614 and if the individual then pursues an employment tribunal claim, average costs would increase by a further £5,872, resulting in a total overall cost of £44,961.

5. Conclusions and implications